Āyurveda

A comprehensive review of chronic kidney disease from the Āyurvedic perspective

Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a threat to global health in general and for developing countries in particular, because therapy is expensive and life-long. Globally, CKD is the 12th highest cause of death and the 17th highest cause of disability respectively (1). Incidence of CKD has doubled in the last 15 years worldwide (2). Chronic kidney disease (CKD), also known as chronic renal disease (CRD), is a progressive loss in renal function taking place over a period of months or years. The diagnosis of CKD population at early stages 1 & 2, when much more can be offered to slow down its progression, is difficult and most patients are diagnosed at stage 5 when modern science offers dialysis or renal replacement. Both these procedures are expensive and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Hence there is a need for seeking docile management options in other systems of medicine to facilitate the patient to survive and lead a qualitative life with a good acquiescence to treatment. In Āyurveda, the disease can be considered as a complication arising from various urinary disorders and systemic disorders. A hampering of the function of basti, i.e. urine formation, results in the accumulation of several noxious products in circulation which need to be excreted. Management is aimed at eliminating these toxins, to protect the accessible renal cells and rejuvenate the quiet cells. The toxins can be eliminated by purification (virecana therapy and basti therapy) or pacification (saṁśamana). The revival of damaged renal cells can be rectified by rasāyana therapy.

Introduction

The world is currently facing a global epidemic of chronic kidney disease. As morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases has decreased, life-expectancy has also increased and chronic degenerative diseases have become more prevalent. CKD is unique amongst chronic non-infectious diseases in that there is an opportunity to continue living comfortably in spite of being terminally ill. The duration of artificial prolongation is largely proportional to the financial resources of the patient or his provider. In India, 90% of patients cannot afford the cost (3) and it has been recently estimated that the age-adjusted incidence rate of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is 229 per million populations (pmp). This number is increasing globally at a rate of 7% every year (4). It is estimated that only 10–20% of ESRD patients in India continue long- term renal replacement therapy (RRT) (5). Over 1 million people worldwide are kept alive on dialysis or with a functioning graft (6). Thus there has been a dramatic resurgence of interest in alternative systems of medicine, particularly Āyurveda, not only in India but all over the world. The revival of interest in this traditional preparation among the developed countries is based on diverse reasons and has many facets.

CKD encompasses a spectrum of different pathophysiological processes associated with abnormal kidney function and a progressive decline in glomerular filteration rate (GFR). The term chronic renal failure (CRF) applies to the process of continuing significant irreversible reduction in nephron numbers and typically corresponds to CKD stages 3-5. Chronic kidney disease may also be identified when it leads to one of its recognised complications, such as cardiovascular disease, anaemia or pericarditis (7). It is differentiated from acute kidney disease in that the reduction in kidney function must be present for over 3 months. Chronic kidney disease is identified by a blood test for creatinine. Higher levels of creatinine indicate a lower glomerular filteration rate and as a result a decreased capability of the kidneys to excrete waste-products. Creatinine levels may be normal in the early stages of CKD, and the condition is discovered if urine analysis shows that the kidney is allowing the loss of protein or red blood cells into the urine. The term end-stage kidney disease represents a stage of CKD where accumulation of toxins, fluid and electrolytes normally excreted by kidney results in the uraemic syndrome. This syndrome leads to death unless the toxins are removed by renal replacement therapy. Often, chronic kidney disease is diagnosed as a result of screening of people known to be at risk of kidney problems, such as those with high blood pressure or diabetes and those with a blood relative who has chronic kidney disease (8).

Āyurveda recommends various preventive measures, e.g. avoiding injury to basti, non-suppression of the natural urges of urination and defecation, following the rules of hygienic living such as dinacaryā, ṛtucaryā, firmly following instructions regarding dietetic practice and timely management of disorders affecting urinary system at the very preliminary stage. Management principles are based on detoxification of the patient by saṁśodhana therapy (virecana and basti) along with use of many medicinal plants which shield the renal cells from damage. If dangerous signs of affliction of the kidney appear, then also this holistic science offers a better disease control by a competent physician with the use of rasāyana drugs (regenerative and rejuvenative) to a psychologically powerful patient.

Aims and objectives

1. To explore the chronic kidney disease from the perspective of Āyurveda.

2. To evaluate the utility of Āyurvedic science in its management.

Materials and methods

Modern texts, classical Āyurveda literature as well as research journals were exhaustibly studied regarding the appraisal of CKD.

Āyurvedic review

In Āyurveda, the term basti seems to represent the unit of urinary system as this word is most widely used in the description of mūtranirmāṇa prakriyā, mūtrāghāta, Mūtrakṛcchra, mūtrāśmarī and prameha samprāpti. Almost all these diseases signify chaos of the urinary system. Basti is one of the most important vital organs (marma) of the body, i.e. its normal functioning is compulsory for the maintenance of life (9). The above fact is strengthened by Ācārya Caraka’s view that its affliction by vātādi doṣa is fatal to that individual (10). Ācārya Suśruta further emphasises the essentiality of normal functioning of basti by excerpting that its damage leads to the demise of the patient (11). In modern science, kidneys are vital organs therefore their counterpart in Āyurveda can be basti. In Āyurveda, CKD has not been described directly by name as naming the disease was not considered of much importance. Rather, the nature of the pathology, condition of doṣa and condition of the patient are to be valued (12). Yet this malady can be very well understood. The ailment appears to be an upadrava (complicated stage) of diseases of the urinary system or other systemic illnesses. Diseases of the urinary system are explained as mūtrāghāta, mūtrakṛcchra, mūtraśmarī. Other systemic sicknesses having deleterious effects on basti (kidney) are prameha (diabetes mellitus), āma doṣa and dhamaṇīpraticaya (atherosclerosis). Contemporary science also considers that illnesses due to diabetic glomerular disease, hypertensive nephropathy, cystic and tubulointerstitial nephropathies are due to infection, drugs, stones, prostate disorders, malignancy or multiple myeloma. The long-term effect of the above mentioned diseases is damage to the kidneys which can be explained as follows:

Mūtrakṛcchra

Difficulty in passing urine usually associated with pain is termed as mūtrakṛcchra. Vitiated by all the three doṣas accumulating in the urinary system (basti) and vitiating it leads to mūtrakṛcchra (13). The nature of pathogenesis is a narrowing of passages in vātaja, inflammation of passage in pittaja, injury in abhighātaja (14), prostatic enlargement in śukraja, obstruction by calculi and their particles in aśmarīja and śarkarāja mūtrakṛcchra respectively (15). Excessive vitiation of the urinary system as in sānnipātika mūtrakṛcchra with full-blown tridoṣaja features signifies extensive damage to the kidneys with its systemic effects. These features are emaciation, thirst, restlessness, changing moods, apathy, delirium, giddiness, fainting and unconsciousness (16). All these features are indicative of a uremic syndrome.

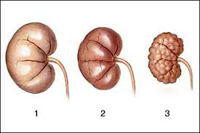

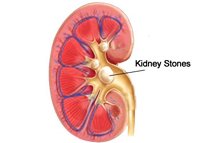

Mūtraśmarī

The word aśmarī means stone. In Āyurveda, the word aśmarī is mainly used for urinary calculi when increased waste-products accumulate in the urinary tract. Vāta in the urinary tract exerts its drying action on kapha, pitta, śukra and mūtra and gives rise to the formation of calculus (17). Longstanding big calculi, if not treated, lead to an obstruction to the passage of urine and deteriorating renal functions, the manifestations of which are anorexia, anaemia, thirst, vomiting, exhaustion, uṣṇavāta (pyelitis & cystitis) (18).

Mūtraghāta

Mūtraghāta signifies the retention of urine along with mild dysuria due to obstruction of the urinary passage. Therefore there is no excretion of urine or mild excretion of urine with difficulty. Mūtraghāta is produced due to vitiation of basti by circulating augmented doṣas (19). Suppression of the urge for micturition in vātabasti, mūtratīta, mūtrajaṭhara and vātakuṇḍialika results in retention of urine. Mūtragranthi (tumour of bladder / prostate hypertrophy) and aṣṭhīlā (malignant prostate hypertrophy) directly obstruct the passage of urine and hence retain the urine. Symptoms of uṣṇavāta include urinary tract infection and thus the associated inflammation results in retention as well as dysuria. Mūtrakṣaya appears to be a prototype of oliguria due to poor hydration status which, if it occurs for a prolonged duration, may impair renal blood flow and thus harms the renal cells. Viḍvighāta is the faecal contamination of urine due to rectovesical fistulae. If this fecal contamination ascends to the upper urinary tract, infection can occur which may lead to renal damage. Bastikuṇḍala gives the impression of atonic bladder in which retention of urine is noticed. If this disease results in complete obstruction of the urinary passage the symptoms described such as thirst, delirium and breathlessness do resemble that of uremic syndrome (20).Chronic retention of urine due to either of the above causes consequences in stasis of the urine. This increases the chance of contagion and formation of urinary calculi which gradually damage the kidneys.

Prameha

Pathogenesis of prameha, exhibits the localisation of vitiated doṣa and duṣya in basti, which connotes the pathological changes (sroto-vaiguṇya) pertaining to this structure (21). Here the doṣaduṣaya sammūrcchaṇā (interaction between vitiated doṣa and duṣaya) takes place (22) which marks the prodromal stage of the disease. The characteristic prodromal symptom pertaining to renal dysfunction is urine being attracted by pipilīkā (glycosuria) (23). If the disease further progresses, it leads to its full manifestation, being represented by its characteristic symptom of increased frequency of urine arises along with turbidity (24), i.e. polyuria with proteinuria, which is suggestive of nephropathy, a remote complication of diabetes mellitus. Reprehensible management at this stage culminates in incurability of the illness (25).

Dhamaṇīpraticaya

The normal dhamaṇī (artery) function of basti is ascertained by an appropriate formation of urine (26). Dhamaṇīpraticaya (atherosclerosis) is characterised by a fullness and thickening of the blood vessels. Dhamaṇīpraticaya of the renal artery results in a condensed blood supply to basti, thus deteriorating its function (27).

Āmadoṣa

Āma is considered to be a product of improper assimilation of dietary constituents. Improper formations of intermediate products of digestion have toxic properties and are treated as foreign compounds to the body (28). Āma results from hypofunctioning of agni, the term relating to both pācakāgni (digestive enzymes) and dhātvāgni (metabolic enzymes). Āyurveda attributes many diseases to āma. Āma occurring due to improper digestion of food is normally not absorbed. Vitiated annavāhi srota enables the āma to pass through the intestinal lining. On entering the rasadhātu, they are distributed to different tissues and get deposited in the specific organ system and produce disease. It is well known that occasionally macro-molecules from improperly digested food get absorbed. These are nutritionally insignificant but can evoke a strong response, leading to formation of immune complexes which, when deposited at a specific place, produce inflammatory changes (29). Thus it appears that āma are the circulating immune complexes. In the description of mūtrakṛcchra, etiological factors producing āma are evident (30). Therefore in the light of the above viewpoint, it can be deduced that āma (immune complexes) deposited in renal parenchyma (e.g. in glomerulonephritis) result in damage to nephrons and may progress to CKD.

Probable samprāpti of CKD

Complicated illnesses of the urinary system and other systemic diseases lead to a vitiation of tridoṣa. The arrival of these augmented doṣas in basti is well described by Ācārya Suśruta when explaining the urine formation process. He illustrates it as a new pitcher submerged in water that is filled with water from all sides in the same way doṣas reach the basti (31). These doṣas damage the basti (kidneys). After digestion, urine is differentiated and separated as a metabolic end-product in basti for excretion (32). A diseased basti is unable to perform this process of differentiation and separation of urine from the essential part. Hence these metabolic excretory end-products which are harmful to the body are retained and circulated everywhere in the body and produce systemic injurious effects (33). A modern pathogenesis of CKD denotes damage to renal cells specific to underlying etiology, e.g. by immune complex deposition, inflammation in certain types of glomerular nephritis or toxin deposition in certain diseases of renal tubules and interstitium. The systemic injurious effects are a consequence of the accumulation of toxins that normally undergo excretion by the kidneys, including protein metabolism, those consequent to the loss of other renal functions, such as fluid and electrolyte homeostasis and hormone regulation and progressive systemic inflammation and its vascular and nutritional complications.

Clinical features of CKD

Stages 1 and 2 of CKD are usually not associated with any symptoms arising from the determination of GFR. However there may be symptoms of underlying renal disease itself or other systemic diseases. If the decline in GFR progresses to stage 3 or 4, clinical and laboratory complications of CKD become more prominent. In CKD virtually all organ systems are affected, but the most evident complications include anemia and the associated easy fatigability, decreasing appetite and progressive malnutrition, abnormalities in calcium, phosphorus & the mineral regulating hormone, calcitriol, PTH and abnormalities of sodium and potassium, water and acid base homeostasis. As this syndrome is the complex segment (upadrava) of various earlier mentioned diseases, the features resembling renal failure are suggestive of a short lifespan. These may be recognised as follows:

• Symptoms, as described in sānnipātaja mūtrakṛcchra, e. g. emaciation, thirst, restlessness, changing moods, apathy, delirium, giddiness, fainting and unconsciousness, indicate stage 5 CKD where toxins accumulate eventuating in uremic syndrome.

• Excessive urinary and stool excretion despite considerably very little intake of food or vice versa (34)

• Excessive urinary excretion in complicated prameha roga (35) resulting in water and electrolytic imbalance

• Excessive fatigue and emaciation in madhumeha (36) due to nutritional and electrolytic imbalance secondary to diabetic nephropathy

• Urine-like smell from the body (37) indicative of smelly urine

• Semi-solid (grathita — ghanībhūta) urine (38) suggestive of proteinuria

• Abnormal colour of the body due to dermatologic disturbance and abnormal color of urine along with fatigue (39).

Prognosis

In Āyurveda the acquaintance of prognosis of disease, i.e. differentiation between curable and incurable diseases is mandatory for a good physician. As CKD is an illness of a vital organ and is also at a complicated stage, therefore in the early stages (i.e. in stages 1 and 2), it may be considered as kṛcchrasādhaya (treated with difficulty). The 3rd and 4th stages may be taken as yāpya (palliable) when significant damage to kidney cells resulting in various biochemical derangements is encountered. At this stage the patient needs to follow a strict regimen otherwise the disease progresses towards definitive incurability. 5th or end-stage renal disease is associated with uremic features and accepted as incurable and immitigable since it spreads to all the organ systems with its destructive effects and is coupled with fatal prognostic features (40).

Management

Modern therapeutics in CKD aims at treating its specific causes. These include optimised glucose control in diabetes mellitus, immuno-modulatory agents for glomerulonephritis, emerging therapies to retard cytogenesis in polycystic kidney disease, reducing intra-glomerular hypertension and proteinuria, adjustments in dietary intake of salt and use of loop diuretics to maintain euvolumia, and management of underlying hypertension. End-stage kidney disease with uraemia requires maintenance dialysis or renal transplantation. As these procedures are associated with significant complications and non-compliance, patients are seeking more modest management options in other systems of medicine.

The primary aim of Āyurveda is promotion of health in healthy individuals followed by treatment of disease. For a healthy urinary tract (basti), Āyurveda advocates constant efforts in maintaining good health, such as avoiding injury, non-suppression of natural urges especially of urination and defecation, steady adherence to the rules of a regimen of hygienic living such as dinacaryā, ṛtucaryā, strictly following instructions regarding dietary protocol and prompt treatment of disorders affecting the urinary system at the very initial phases (41). In Āyurveda too, the disease bastikarmavighāta (CKD) appears to be a complication of other diseases such as prameha, dhamaṇīpraticaya, āmadoṣa, etc., therefore curing these primary illnesses can alleviate the early stages of CKD, but an advanced stage of CKD is a severe complication which requires quick management since it is more life-threatening and agonising for the patient (42).

The causes of CKD are very well managed in Āyurveda. The circulating vitiated doṣa in CKD can be eliminated by virechana therapy (43). Moreover, that basti therapy, in combination with various drugs capable of managing the situation pertaining to sannipāta, is also indicated. It performs a variety of functions, e.g. evacuation, pacification and checking of doṣa and maintains the lifespan of the patient (44). Śarakashaadi niruha basti, śatāvarī-gokṣurādi niruha basti and pītadaru siddha taila anuvasana, balāriṣabhakādi anuvāsan basti are depicted in bastigata roga (45). Ācāryas have mentioned the treatment of lethal diseases with the use of rasāyana therapy by a proficient physician (46). Thus even end-stage renal disease, a fatal condition (ariṣat), can be managed with rasāyana therapy. It promotes the rejuvenation and regeneration of tissues and strengthens the cognitive functions and is capable of removing diseases (47). Some experimental findings also show that rasāyana therapy harmonises the functioning of organs by modulating neuro-endocrine mechanisms; they strengthen the host’s general resistance by stimulating the immune function. Thus increased immuno-competence improves the quality of tissues so that they are able to handle the effects of external and internal stress in a better way. There are several herbs with rasāyana effects on the urinary system, such as punarnavā (mūtravirecanīya mahākacṣāya), gudūcī, śatāvarī (kaṇṭaka pañcamāla), gokṣura (48). In addition, Ācārya Suśruta has advised the performance of japa (chanting the name of God) and tapa (penance) during the end-stages of disease. This improves the cognitive functions. It has been proved by intricate experiments that the brain can influence the immune system, which in turn can send impulses back to the brain by means of secreting hormones and neuropeptides enabling the tissues to fight against stress.

Conclusion

Chronic kidney disease is the slow loss of kidney function over time. Chronic kidney disease slowly gets worse over months or years. In Āyurveda, the ailment is considered an upadrava (complicated stage) of diseases of the urinary system (mūtrāghāta, mūtrakṛcchra, mūtraśmarī) or other systemic illnesses such as prameha (diabetes mellitus), āma doṣa, dhamaīpraticaya (atherosclerosis). The augmented doṣa arrives at basti and vitiate it. Hence, the ailing basti stops its function of differentiation and separation of urine from essential parts, thus retaining harmful metabolic excretory end-products which circulate everywhere in the body and produce detrimental effects. In the early stages, the disease may be considered kṛcchrasādhaya while in the later stages it becomes yāpya and incurable. Āyurveda advocates its management by purification therapy (saṁśodhana), pacification therapy (saṁśamana) and rasāyana therapy. Rasāyana therapy along with psychological harmony has the potential of apparently curing the illness even at the end-stages by a skilled physician. A strict dietary regimen is always required by the patient throughout life. By these therapies, the progress of the illness can be restricted, renal functions are improved and systemic effects of raised nitrogenous waste-products are blocked, enabling the person to live an enhanced and improved quality of life.

References

1. Perico N, Remuzi G. Chronic kidney disease: a research and public health. Nephrology Dialysis transplant (july 2012). [Online] Available from :http://www.ndt.oxford journals.org/content/27/suppl 3/iii19 [Accessed on 30th July 2014].

2. Dash SC, Sanjay K. Incidence of chronic kidney disease in India. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation (January2006). [Online] Available from: http://www.ndt.oxford journals.org/content/21/1/232 [Accessed on 30 th July 2014].

3. Ibid. [Accessed on 30th July 2014].

4. Singh et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of CKD in India – results from SEEK study. BMC Nephrology Journal 2013. [Online] Available from :http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/14/114 [Accessed 15th July 2014].

5. Veerapan et al. Chronic kidney disease: Current status, challenges and management. API [Online] Available from :http://www.apiindia.org/medicine_update_2013/chap130.pdf [Accessed on 30th July 2014].

6. Lysaght MJ. Maintenance dialysis population dynamics: Current trends and long term implications, Journal of American Society of Nephrology 2002; 13: S37-40.

7. Chronic kidney disease. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Online] Accessed from: http://www./en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronic_ kidney_disease [Accessed on 30th July 2014].

8. Ibid. [Accessed on 30th July 2014].

9. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.). Caraka saṁhitā, Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Siddhi sthāna Ch. 9, Śloka 3. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 716.

10. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.). Caraka saṁhitā, Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Cikitsāsthāna Ch. 26, Śloka 4. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 597.

11. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Nibandha saṁgraha, commentary of Dalhana. Śarirasthāna Ch. 6, Śloka 25. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia, 2003 , p. 373.

12. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 18, Śloka 44-46. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 108.

13. Vṛddha Jīvaka. Sharma Hemraj Pandit (ed.) Kāśayapa saṁhitā. Cikitsāsthāna Varanasi: Choukhamba Sanskrit Series; 2010 re-print, p. 120.

14. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Uttara tantra, Ch. 59, Śloka 4-8. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 792.

15. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā,. Cikitsāsthāna Ch. 26, Śloka 37-41. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Praka-shan; 2005 re-print, p. 599.

16. Vrrddha Jnvaka. Sharma Hemraj Pandit (ed.) Kāśayapa saṁhitā. Cikitsāsthāna Varanasi: Choukhamba Sanskrit Series; 2010 re-print, p. 120.

17. Vāgbhatta. Paradakar Shastri (ed.) Asṭāṅga hṛdaya. Nidāna sthāna Ch. 9, Śloka 6. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Praka-shan; 2011, p. 498.

18. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Nidāna sthāna Ch. 3, Śloka 16-17. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 279.

19. Vāgbhatta. Paradakar Shastri (ed.), Asṭāṅga hṛdaya. Nidāna sthāna Ch. 9, Śloka 3. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Praka-shan; 2011, p. 498.

20. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Siddhi sthāna Ch. 9, Śloka 48. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 719.

21. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Nidāna sthāna Ch. 4, Śloka 8. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 213.

22. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 21, Śloka 33. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 105.

23. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Cikitsāsthāna Ch. 6, Śloka 14. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 446.

24. Vāgbhatta. Paradakar Shastri (ed.), Asṭāṅga hṛdaya. Nidāna sthāna Ch. 10, Śloka 7. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Praka-shan; 2011, p. 502.25. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Nidāna sthāna Ch.4, Śloka 8. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 213.

26. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 20, Śloka 17. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 115.

27. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Śarīrasthāna Ch. 9, Śloka 7. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 384.

28. Vāgbhatta. Paradakar Shastri (ed.), Asṭāṅga hṛdaya. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 13, Śloka 26. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2011, p. 216.

29. Wigger RC, Cochrane C G. Immune complex mediated biologic effects. New England Journal of Medicine 1981; PMID-640327. 304 (9): 518-20.

30. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Cikitsāsthāna. Ch. 26, Śloka 32. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 599.

31. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Nidāna sthāna Ch. 3, Śloka 23, 24. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 279, 280.

32. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapānnidutta. Cikitsāsthāna. Ch. 25, Śloka 17. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 515.

33. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Śarīrasthāna. Ch. 6, Śloka17. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 333.

34. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapānnidutta. Indriyasthāna. Ch. 7, Śloka 21, 22. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 366.

35. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. śarīrasthāna Ch. 33, Śloka 8. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 144.

36. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Indriyasthāna. Ch. 9, Śloka 8. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p.368.

37. Ibid. Indriyasthāna. Ch. 2, Śloka 13, p.357.

38. Ibid. Indriyasthāna. Ch. 6, Śloka 11, p.364.

39. Ibid. Indriyasthāna. Ch. 1, Śloka 22, p.356.

40. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Sūtrasthāna. Ch. 10, Śloka 11-20. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 66, 67.

41. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Siddhi sthāna Ch. 9, Śloka 9-10. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 718.

42. Vāgbhatta. Paradakar Shastri (ed.), Asṭāṅga hṛdaya. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 13, Śloka 26. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Praka-shan; 2011, p. 363.

43. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Cikitsāsthāna Ch.33, Śloka 3,32. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 2003, p. 515, 519.

44. Ibid. Cikitsāsthānā Ch.XXXV, Śloka 3,4,6, p.527.

45. Agniveśa. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Caraka saṁhitā. Dīpikā commentary by Cakrapāṇidutta. Siddhi sthāna. Ch.9, Śloka 8. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2005 re-print, p. 717, 718.46. Suśruta. Trikamji Ācārya (ed.) Suśruta saṁhitā. Nibandha Saṁgraha commentary of Dalhana. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 33, Śloka 3. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia, 2003 , p. 144.

47. Ibid. Sūtrasthāna Ch. 1, Śloka 7, p.3.

48. Vāgbhatta. Paradakar Shastri (ed.), Asṭāṅga hṛdaya. Uttara tantra, Ch. 9, Śloka 56,57. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan; 2011, p. 927.

Glossary of Āyurvedic terms

Āmadoṣa — disease occurring due to mal-digestion.

Aṣṭhīlā — a hard and fixed growth which leads to obstruction of urerthra and rectum.

Abhighātaja — traumatic

Anuvasana — therapy in which medicated oil is inserted per anum.

Aśmarīja — arising due to stone

Balāriṣabhakadi — medicated oil prepared with essence of Sida cordifolia, etc.

Basti — urinary system

Basti therapy — the therapy of pañcakarma in which medication is given through rectal route.

Bastikarma vighāta — suppression of renal function.

Bastikuṇḍala — the disease in which the bladder displaces in upward direction.

Bīja-doṣa — chromosomal abnormalities.

Dhamaṇīpraticaya — thickening of vessels.

Dhātvāgni — digestive enzymes disseminated throughout every tissue.

Dinacaryā — balanced and healthy daily routine.

Doṣa — the important biological factor for maintenance of body which also has the independent power of producing diseases in abnormal states.

Duṣya — bodily tissues

Grathita mutra — semi-solid urine.

Kṛcchrasādhaya — diseases which are treated with difficulty.

Kapha — the biological factor which supports the body by performing anabolic functions.

Mala — products of excretion.

Marma — sensitive points representing a great concentration of the body’s vital force.

Mūtra — urine

Mūtrāaghāta — obstruction to the passage of urine

Mūtragranthi — small, round, immobile, painful, stony hard swelling near urethral sphincter which obstructs urine flow.

Mūtrajaṭhara — suppression of urination for long time which leads to distension of urinary bladder.

Mūtrakṛcchra — painful micturition.

Mūtranirmaṇa prakriyā — process of urine formation.

Mūtrāśamarī — renal stones.

Mūtratīta — distension of bladder and difficulty in passing urine after withholding urination for a long time.

Pācakāgni — digestive enzymes.

Prameha — the disease in which there is an increased frequency of turbid urine.

Pitta — the biological factor supporting the body by performing functions such as coloring, digestion, metabolism, vision, intelligence and generation of heat.

Pītadaru siddha taila — medicated oil prepared from the essence of Cedrus deodara, etc.

Rasāyana drugs — regenerative and rejuv-enative drugs.

Roga — disease.

Ṛtucaryā — it is description of regulations of seasonal regimen.

Śamana — disease management that concentrates on palliation of the symptoms of disease.

Samprāpti — pathogenesis, the complete route of manifestation of disease.

Saṁssodhana — disease management that primarily focuses on the elimination of the source of disease.

Srotas — the channel transporting nutrients in the body.

Srotovaiguṇya — the pathological changes in channels.

Śukra — semen

Śukraja — arising from semen.

Śarkarāja — occurring due to little stones.

sānnipātika — abnormal conglomeration of vāta, pitta, kapha.

Sānnipātaja — occurring due to abnormal accumulation of vāta, pitta and kapha.

Upadrava — complications.

Uṣṇnavāta — the disease in which there is pain and burning sensation in urinary tract.

Vāta — the biological factor which supports the body by performing functions such as movement, perception, separation and retaining.

vātakuṇḍialika — obstructed urinary passage resulting in broken curved and spiral urination.

Vātabasti — painful retention of urine.

Viḍvighāta — faecal contamination of urine.

Virechana — therapeutic purgation.

Yāpya — palliable.

Dr. Monika Kumari is a Ph. D.Scholar and Dr. Priti Patil is an M.D. Scholar; Dr. Asit Kumar Panja is Assistant Professor; Dr. K.L. Meena is Associate Professor and Head at the Dept. of Basic Principles, National Institute of Ayurveda, Jaipur.

Share with us (Comments,contributions,opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH,and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.