The Aim of Medicine

Āyurveda in the light of the Integral Yoga

An address at Matagiri, USA, 24th November, 2006.

Editor's note

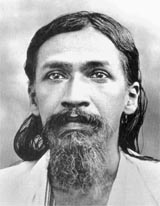

This talk is about the truth of Āyurveda. It has gems on Āyurveda that many physicians trained in Āyurvedic medicine have lost sight of. It is also an eye-opener for what to expect when you take Āyurvedic medicine.Dear Friends, it is a great privilege for me to be speaking to you today. I have come to the US only recently but this will be the first occasion for me to speak on the subject of Āyurveda and it is of great significance to me personally that this is happening not in any ordinary location or on just any ordinary occasion. This is a very special place and today happens to be a very special occasion. This place is Matagiri, the Mother’s mountain, and we are here today to celebrate Sri Aurobindo’s Siddhi Day. I therefore consider that this is not merely a coincidence but a sure sign that I have the blessings of the Master and the Grace of the Mother in my work as an Āyurvedic healer. I have a feeling that this is not merely a continuation of my career but in fact a new beginning, the beginning of my work for the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. And therefore, I would like to make this presentation a humble offering to the Divine Mother and I accept with complete gratitude and absolute humility this rare privilege that has been given to me without even my asking for it ... this privilege of serving them.

The topic of my presentation today is ‘Āyurveda in the light of the Integral Yoga’. Now both Āyurveda and Integral Yoga are vast, complex and multi-faceted subjects. Due to my long association with Āyurveda, I can claim to be an expert in this field. However, I cannot claim to be an expert in the field of Integral Yoga. In fact there are many experts in the field of Āyurveda. But I wonder if there are any in the field of Integral Yoga except for the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. Therefore, today we will not go deeply into either Āyurveda or the Integral Yoga. Rather what I will try to do today is to give you a brief introduction to the real nature of Āyurveda and try to show you in what way Āyurveda reflects or is a reflection of some of the fundamental teachings of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother... and how Āyurveda can help and support the efforts of those who are engaged in the sādhāna of the Integral Yoga. In particular I have drawn most of my inspiration from the words of the Mother and Her teachings related to health and healing, because in the short time that I have spent in researching, I have been amazed by the amount of practical wisdom and extraordinary insights that the Mother and Sri Aurobindo bring to this topic. In fact I am convinced that had I been introduced to the teachings of Mother and Sri Aurobindo earlier, I would have met with far greater success in my practice as an Āyurvedic physician and it would also have been a much more interesting experience.

Most people are led to believe that Āyurveda is simply pulse diagnosis, that it is some miraculous or magical form of diagnosing the patient. In fact even in the US there are public demonstrations where there will be a huge audience and somebody will walk around and take your pulse or ask to stick out your tongue and tell you your entire medical history. There are people who do something like this. However this kind of pulse reading or diagnosis is not Āyurveda. It is actually called Nāḍī Vijñāna. But Āyurveda is something much more and it does use some kind of pulse diagnosis as a technique to evaluate the health of the patient but it is not merely limited to pulse diagnosis.

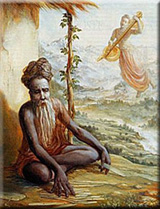

There is another misconception of Āyurveda — that it is simply herbal medicine and that its origin lies in the villages of India where some villager who specialized in and made his living by healing sick people would go into the forest, collect some herbs, bring them back, crush them in a small pot and feed the paste or apply it to the patient. But the roots of Āyurveda are not found in the village sāmans nor in the practices of local witch doctors. The origin of Āyurveda lies rather in the ashrams and the hermitages of the Ṛṣis or sages of India and it is a direct product of the consciousness of the self- realized, divinized Ṛṣis. In fact Āyurveda is nothing but the way of life adopted by the Ṛṣis of India in order to maximize their life-potential and to maintain their health at the best possible level because this body was the first requirement and an essential prerequisite for a successful attainment of their spiritual realization.

The origin of Āyurveda

This also explains the origin of the term Āyurveda. The term Āyurveda is composed of two root words Āyu and Veda. Āyu stands for life and Veda stands for knowledge. But as followers of Mother and Sri Aurobindo must already know, Veda does not mean just any knowledge but knowledge that originates from the Divine Consciousnessand becomes the revelation transmitted by the Ṛṣis. Ordinary knowledge is of temporary value and must be discarded with changing times or as time goes by. However the body of knowledge to which we give the name of Veda is something that by its very definition means something of a universal and eternal value which does not loose any relevance with the passage of time.

So we must understand that Āyurveda is not a system of medicine that was developed merely on the basis of reason. Āyurveda, as I have already mentioned, is more of the nature of intuitive revelation based upon a direct perception of the principle of right living and right conduct. What I would like to stress is that Āyurveda is not merely a science which was developed through a process of experimentation and trial and error solely on the basis of unaided reason. In addition to the methods of experimentation and observation, which are the sources of knowledge in the modern sciences, Āyurveda accepts concentrated meditation (Dhyāna) and intuition (Jñāna) as a method of acquiring knowledge. So it was not as if the Ṛṣis were experimenting with different plants or that they were trying out various healing techniques. Rather what was revealed to them as direct intuitive knowledge first, was then translated by them into standard formulas and also verified by them through observation and experience.

At this juncture we can make out the first and probably the most fundamental meeting ground between Āyurveda and the Integral Yoga, which is that Āyurveda is a product or a revelation that results directly from the consciousness of the self-realized and divinized Ṛṣis, a consciousness and poise of being that is a fundamental characteristic of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. It is on this basis that one can see the striking similarities between the Ayurvedic approach of the ancient Ṛṣis towards the maximization of life-potential and health, and the approach of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo towards the same.

So to sum it all up, the fundamental truths of Āyurveda, the essential principles, were first revealed to the Ṛṣis. These were then verified as well as turned into various details of practice by what we would consider to be scientific and systematic through observation, experimentation and analysis over a period of many thousands of years. Reason was not used to arrive at knowledge, it was used to verify knowledge which was intuitive and something revealed.

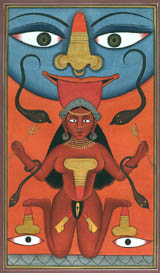

For example one of the most fundamental principles or essential truths of Āyurveda is the classification of individual human nature according to the presence, functioning and relative predominance of what are referred to as tridoṣas which can be translated into English as the three functional intelligences called Vāta, Pitta and Kapha. The principle of Vāta in the body is symbolically represented by the conceptual image of air. It is responsible for all the movements in the body right from the most seemingly insignificant and involuntary movements to all the movements of which we are conscious, e.g. talking, walking, perceiving — any movement or motion is the result of Vāta. The principle of Pitta can be symbolically represented by the conceptual image of fire. It is responsible for all the transformations in the body, both mental (digesting information) and physical (digesting food, e.g. food getting transformed into body products, etc.) Lastly the principle of Kapha can be symbolically represented by the conceptual image of a viscous fluid. It is responsible for the weight of the body, giving the body a definite shape, etc.

Now these three functional intelligences are subtle in nature, i.e. they cannot be perceived in their essence by the senses or by any instruments or through any kind of experimentation or through theoretical reasoning. Rather the ancient Ṛṣis arrived at the knowledge of tridoṣas through direct intuition, but today using this knowledge we are able to successfully diagnose the physiological constitution of every human being and also to prescribe remedial therapies. This example illustrates how intuitive knowledge is applied through reason. This, in essence, describes the origin of Āyurveda and also the reason why it is not simply any knowledge or vidyā but actually a Veda.

The purpose of Āyurveda

But even if we accept this as the origin of Āyurveda, we could ask the question, why? Why did the Ṛṣis, whose primary preoccupation in life was to elevate their consciousness to unite with the Divine, to pass from death to immortality, to pass from suffering to bliss and to pass from ignorance to omniscience, take all the trouble of giving the world Āyurveda when they had already given to it the Veda of immortality, bliss, and omniscience? Their purpose in doing so was twofold. Āyurveda, as we have already noted, is the Veda of life and its aim is to maximize human life-potential and at the same time optimize human health. By giving this wisdom the Ṛṣis wanted to help alleviate the common widespread pain and misery of the common man. For the common man, suffering is synonymous with and indistinguishable from bodily pain and physical disease. The common man hardly lives in his mind, let alone his soul. We are all so completely identified with our bodies that when the body suffers distress, disease and decay we think that it is we who suffer disease, distress and decay. When one is in such a condition spirituality, philosophy, idealism or ethics make very little difference. In their compassion for ordinary human beings, the Ṛṣis knew that the help required by humanity, the crying need and desperate necessity of struggling humanity, was for a truth that could help alleviate this physical suffering. This was the first and foremost purpose behind the revelation of Āyurveda through the Ṛṣis.

The second purpose of Āyurveda is that it served as a help in the spiritual quest for those who followed in the footsteps of the Ṛṣis, those who, like the Ṛṣis, sought the Divine truth, immortality and bliss. Now the Ṛṣis were concerned primarily and almost exclusively with obtaining the spiritual Siddhi that would lead them to the realization of the supreme truth. However, to get to that point, to achieve this objective, to attain this realization there was one fundamental requirement, one basic necessity. Can anyone tell me what this is? What is the one basic requirement for spiritual realization?

(Response from audience)

But there is one requirement which is at the basis of all these and it is so obvious that we take it for granted. The basic thing that you need to attain the spiritual goal or any goal for that matter is life. We have to value and treasure life, as it is life that gives us the opportunity to gain self-realization. We live life, but we don’t value it. Each moment is so precious. We are really unconscious of life, that we are alive and that it is such a miracle to be alive.

But the Ṛṣis understood that life was not an end in itself but a means to gain immortality. In fact, this, according to the Ṛṣis was the main purpose of life and the Mother has said:

“Expect nothing from death. Life is your salvation. It is in life that you must transform yourself. It is upon earth that you must progress and it is upon earth that you realise. It is in the body that you win the Victory (1).”

However, we all know that life is short and also extremely uncertain. The ancient Ṛṣis recognized and took account of this grim reality. They knew that the path of yoga was a difficult one and that achieving the goal of Yoga might even take several lifetimes. But what if the seeker aspired to realize the Divine truth in this life? It would then be necessary to maximize the life-span of the individual, to prolong life, and to maintain best possible health so that the aspirant could attain to the goal. For this reason, the Ṛṣis sought for, found and then conferred upon those who followed in their footsteps the Veda of Life, so that they may be able to surmount the chief obstacles of death, disease and decay that beset the path of all spiritual seekers. This is the second purpose of Āyurveda.

This is of particular relevance to those of us who are on the path of Yoga. We all need to have a healthy life to pursue the path of Yoga. If we have an unhealthy life, we would be concentrating more on our ailments rather than on our Yoga. And this is perhaps one of the most important differences between Āyurveda and modern medicine, in fact any other system of medicine. While modern medicine seeks only to maintain a ‘normal’ functioning of your health, Āyurveda does not stop there. It’s aim is to maximize your life-potential and to do it precisely in such a way that in doing it we begin to open more and more to the spiritual aspect of our being, because not only is the goal of Āyurveda spiritual but also the means it uses to enhance life and health are spiritual — not spiritual in a religious sense, but in a Yogic sense. So with the help of Āyurveda the flowering of our health inevitably brings us more and more in touch with our spirit, our innate intelligence and wisdom and enables us to live more and more constantly out of that growing awareness.

This spiritual essence and goal of Āyurveda is summed up in one word and that is Svastha. This is the ultimate goal of Āyurveda. In ordinary parlance, this word has been translated as merely health. However, there is in fact a deeper, inner meaning of the term. The spiritual or Yogic meaning of the term Svastha surpasses the simplistic notion of ‘freedom from illness’ or a ‘positive state of well-being.’ Instead it denotes a state of being established in one’s Self. The word Svastha is composed of two Sanskrit root words Sva and Stha. Sva means ‘Self’ and Stha means ‘to be established in’. For example, in the Bhagavad Gītā, Krishna says “Yogastah kuru karmāṇi”, which means “Established in Yoga, do thou thy actions”. Here Yoga – stha means to be established in Yoga and similarly Sva-stha means to be established in one’s Self. And Self here does not mean the superficial ego or simply the most outward physical body. Self implies one’s essential being which has been variously referred to as one’s soul, Consciousness or Ātmā, or one’s True Self. In fact, even the word Svastha is used in the Gitaa as well, in the very same sense of being established in the True Self.

To be established in one’s Self is to be consciously that Self which we really are. Essentially, this is the highest and innermost meaning of health in Āyurveda. All other definitions of health are secondary to this notion of Svāsthya, the condition of being Svastha, the condition of being established in one’s Self. So what does this really mean, being established in one’s Self? As some of you may already know, ancient Indian spirituality had long ago arrived at the truth that all existence and each individual being was the manifestation of the dual principle of Puruṣa and prakṛti. Prakṛti is nature and it represents all within us that is ever-changing, impermanent, everything about us that is in a constant state of ceaseless mutation. This is true as much about your physical body as it is about your sensational, emotional nature as well as your mental nature. Your physical body is constantly changing, so are your feelings, emotions and sensations. Similarly, your mental nature, composed of your thoughts, your ideas and your conceptions, is also one constant whirlwind of ever changing forms. All this is your prakṛti.

At the same time, there is something about you that is constant, unchanging, permanent and immutable. This unchanging, eternal ‘You’ is the Puruṣa. It is who you really are. It is your Self. Thus, to be established in your self is to be consciously this eternal unchanging Puruṣa. It is to cease to be identified with our prakṛti, our nature, and to have realized our identity with our Puruṣa, to be established in our Self. In ordinary life when we are identified with our nature, then our nature essentially is functional without us exercising any conscious control over it. For example, if at a given point of time you feel angry, you never realize that anger is simply a vibration or a disturbance in your outer nature. You automatically assume that you are angry or say to yourself that you are angry. In this situation, you will allow anger to manifest itself without any control over it. In the same way if you are not conscious of yourself, if you are not established in yourself, any movement in your nature will manifest itself without you, the Puruṣa, exercising no control over it. When this lack of control reaches its extreme manifestation on the physical plane, it becomes a disease. In the Integral Yoga, Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have stressed on the different planes of one’s nature and also the fact that at each plane of our nature there is a Puruṣa or a power of the spirit that presides over this plane. Sri Aurobindo and the Mother have given us broad classifications of our individual nature. There is a physical nature — annamaya prakṛti. Then there is a vital nature — the prāṇamaya prakṛti and there is also the mental nature or the manomaya prakṛti.

In the words of Sri Aurobindo:

“Over each grade of our being a power of the spirit presides; we have within us and discover when we go deep enough inwards a mind-self, a life-self, a physical self; there is a being of mind, a mental Purusha, ex-pressing something of itself on our surface in the thoughts, perceptions, activities of our mind-nature, a being of life which expresses something of itself in the impulses, feelings, sensations, desires, external life-activities of our vital nature, a physical being, a being of the body which expresses something of itself in the instincts, habits, formulated activities of our physical nature (2).”

Essentially what this means is that there is hidden behind physical nature the annamaya prakṛti, a presiding yet veiled power of the Spirit, the annamaya Puruṣa. Similarly behind the vital nature, the praanamaya prakṛti, there is a praanamaya Puruṣa and behind the manomaya prakṛti, the manomaya Puruṣa or the mental being.

In ordinary life, the Puruṣa on each plane is aware only of the nature and unconscious of itself. As a result, identified with nature, it cannot exercise any control over nature. We are born, live and die, thinking that we are this nature. But, in the light of the teachings of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, I would venture to propose that to be Svastha is to be conscious of one’s Self, one’s true being, on each plane of one’s nature and to be established in the self on each plane.

But for the ordinary human being, as well as the aspirant, this state of Svastha, interpreted as being established in one’s Self or Ātmā, is not easily attainable. In fact this ideal Svastha is synonymous with the goal of Yoga, which is Self-realization. So then what does Svastha mean to ordinary folks? For the ordinary human being as well as the spiritual aspirant, who has not yet attained to the goal of Self-realization, the goal of Āyurveda is to try and attain and to maintain a proper balance and a harmonious, coordinated functioning of the body, senses, heart and mind of an individual as far as it is possible.

According to Āyurveda, there are four basic constituents of life (Āyu) and these are the physical body, the senses, mind and heart, i.e. the overall psychological strength and the soul. When the soul or Ātmā comes in contact with these four then the result is life. In Charaka saṁhitā there is a śloka which defines life as follows — ”śarīrendriya sattvātma saṁyogo āyuḥ saṁjñitam." This śloka gives the definition of the meaning of the word Āyu. Śarīra means the physical body, indriya means the senses, sattva refers to a combination of mind and heart — overall psychological strength and Ātmā means soul or Self. Here, according to this śloka, Āyu is defined as the union of the soul with the mind, body, heart and senses. This is true of all life, even you and me. Conversely we can say that death is defined as the point where the soul separates from the śarīra, sattva and indriya.

So ordinary human life, when all these are in proper balance and function in a harmonious coordination is healthy life. When there is an imbalance in these, i.e. the physical body, the senses, mind, heart, and soul individually or collectively, we become unhealthy. This is the main cause of illness. Now what really unites these different elements, what really brings them together and gives to them cohesiveness, the common thread that runs through all parts of the nature is the Ātmā. Therefore our outer being and our nature can be harmonious to the extent to which the different parts of the being and nature are in touch with the soul. In fact the Mother says:

“An illness of the body is always the outer expression and translation of a disorder, a disharmony in the inner being; unless this inner disorder is healed, the outer cure cannot be total and permanent” (3).

She says to look for the inner causes of, disharmony much more than the outer ones. It is the inside which governs the outside. She says that illness, without any exception, is the expression of a break in the equilibrium. As regards the physical body, if all the organs, all the members and parts of the body, are in harmony with one another, then there is perfect health. But if there is the slightest imbalance anywhere, immediately one gets just a little ill or quite ill or even very badly ill. She also says that, to the equilibrium of the body one must add the equilibrium of the vital and the mind. For one to be able to do all kinds of things with immunity, one must have a triple equilibrium, She says — mental, vital and physical — and not only in each of the parts but also in the three parts in their mutual relations.

Āyurveda provides us with a complete understanding of what is life-sustaining and what is not, not just for the physical body, but also our mind, heart, senses and the soul. This includes a description of the kind of diet, lifestyle and behavior that is optimal for well-being, the ideal environment and the herbal rasāyana that are good or bad for each of these aspects of health. There is great detail on each of these modalities. For example, what to eat, when to eat and how to eat are a part of the dietary recommendations. The text also includes recommendations for nurturing relationships and living as a part of the human community, and not only the human community, but also how to stay in tune with nature or the environment.

Let us go further into what the Mother says about how illnesses are caused and which are the expressions of inner disharmony and disequilibrium. She says that there are two kinds of disequilibrium — functional and organic. If the organ itself is in disequilibrium, it is an organic disequilibrium, i.e. the organ is ill or badly formed or it is not normal or an accident has occurred to it. But the organ may be in very good condition, all your organs may be in very good condition, but still there is an illness, as they do not function properly, there is a lack of balance in the functioning — this is functional imbalance. The Mother says that illnesses due to functional imbalance are cured much more easily than others but that does not mean that organic imbalances are incurable but it is more difficult.

She gives an example to explain this:

“If each one [organ] does its duty and works normally and if all move together in harmony at a given moment and in the right way ... they are in good harmony with one another, good friends, in perfect agreement, and each one fulfilling its task, its movement at the right time, in tune with the rest, neither too soon nor too late, neither too fast nor too slow, indeed, every one going all right, then you are marvellously well! Suppose now that one of them, for some reason or other, happens to be in a bad mood: it does not work with the necessary energy, at the required moment it goes awhile on strike. Do not believe that it alone will fall ill: the whole system will go wrong and you will feel altogether unwell. And if, unfortunately, there is a vital imbalance, that is, a disappointment or too violent an emotion or too strong a passion or something else upsetting your vital, that comes in addition. And if furthermore your thoughts roam about and you begin to have dark ideas and formulate frightful things and make catastrophic formations, then after that you are sure to fall ill altogether.... You see the complication, don’t you, just a tiny thing can go the wrong way and thus through an inner contagion can lead to something very serious. So what is important is to control things immediately. One must be conscious, conscious of the working of one’s organs, aware of the one that does not behave very well, telling it immediately what is to be done to set itself right.... Suppose for example, your heart begins to throb madly; then you must make it calm, you tell it that this is not the way to act, and at the same time (solely to help it) you take in long very regular rhythmic breaths, that is, the lung becomes the mentor of the heart and teaches it how to work properly. And so on. I could give you countless examples (4).”

Likewise, Āyurveda is very strongly oriented towards using the power of “Self” (Ātmā-Śakti) and using it for auto-suggestion and healing. In ancient times, the Ṛṣis believed very strongly in using the inner power, along with precautionary measures and remedies in curing one’s illness. Every cell in your body is totally aware of how you think and feel about yourself. Our mind is connected to the whole body through minute channels called the manovaha srotas.

According to Āyurveda, our thoughts and our feelings influence the body via two kinds of mechanisms, the nervous system and the circulatory system. The brain reaches into the body via the manovaha srotas or the nervous system. This allows it to send nerve impulses into all the body’s tissues and influence their behavior. The brain can thus affect the behavior of the immune system with its nerve endings extending to the bone marrow (the birth place of white cells), the thymus, spleen and lymph nodes. It also reaches the glands of the endocrine system, bones, muscles, internal organs and even the wall of the veins and arteries. It can also influence the behavior of the heart with its nerve endings penetrating the heart tissue, thus affecting the heart rate. It also manufactures thousands of different kinds of chemicals and releases them into the bloodstream. These chemicals circulate throughout the body and influence the activity of the body tissues. The cells of the body have receptors on their surfaces that function somewhat like satellite dishes. These receptors receive the chemical message being released by the brain and act accordingly. Research into how the brain can influence the immune response has given rise to a new field called psycho-neuro-immunology (PNI) and this has brought hope to people dealing with such difficult illnesses as cancer, AIDS, chronic fatigue syndrome, etc.

But here a question arises whether the power of auto-suggestion can work just by itself all the time? Āyurveda believes in using the power of auto-suggestion along with precautionary and remedial measures. Mother gives a wonderful explanation to this saying that, “it is very easy if we know one thing, that the method we use to deal with our body, maintain it, keep it fit, improve it and keep it in good health, depends exclusively on the state of consciousness we are in; for our body is an instrument of our consciousness and this consciousness can act directly on it and obtain what it wants from it.

So, if you are in an ordinary physical consciousness, if you see things with eyes of the ordinary physical consciousness, if you think of them with the ordinary physical consciousness, it will be ordinary physical means you will have to use to act on your body.... And as the vast majority of human beings, even in the Ashram, live in a consciousness which, if not exclusively physical, is at least predominantly physical, it is quite natural for them to follow and obey all the principles laid down by physical science for the care of the body (5).”

However the Mother also draws a clear distinction between Āyurveda and modern medicine. She says that:

“Allopaths ordinarily cure one thing, only to the detriment of another.

Ayurvedic doctors do not usually have this drawback. That is why I recommend them (6).”

So the Mother actually recommends Ayurvedic physicians. Allopathic treatment results in a vicious cycle wherein the cure itself leads to

another disease. Even Sri Aurobindo says that:

“Medical science has been more of a curse to mankind than a blessing ….it has weakened the natural health of man and multiplied individual diseases; it has implanted fear and dependence in the mind and body; it has taught our health to repose not on natural soundness but a rickety and distasteful crutch compact from the mineral and vegetable kingdoms (7).”

However Āyurveda takes a completely integral approach to interdependent parts of a single system. Its primary concern is to examine what set of elements in nature are out of balance with the rest and it seeks to bring back this balance. Also, the means that it employs to achieve this objective, means such as prāṇāyāma, meditation, diet, lifestyle changes, are all directed ultimately towards bringing the patient closer towards the Ayurvedic ideal of Svāsthya, because all of these practices are not just healing techniques which increase and protect your Āyu or Life but also yogic practices which lead you towards Self-realization.

And this is what I would like to stress in conclusion, that Āyurveda is not simply another system of health and healing. It is a Veda — the Veda of life, and its essential purpose is to maximize the life-potential of each human being in order to lead them closer to the Spiritual Truth of their being, towards Self-realization. I have given you a little taste of Āyurveda so far, and we have only scratched its surface. We have also only begun to see how Āyurveda is relevant to the Integral Yoga in particular. The scope for collaboration is immense.

Sri Aurobindo has said that:

“Life is the field of a divine manifestation not yet complete: here, in life, on earth, in the body... we have to unveil the Godhead; here we must make its transcendent greatness, light and sweetness real to our consciousness, here possess and, as far as may be, express it. Life then we must accept in our Yoga in order utterly to transmute it; we are forbidden to shrink from the difficulties that this acceptance may add to our struggle (8).”

A ‘divine life in a divine body’ is the aim of the Integral Yoga, and Āyurveda, the Veda of Life, can be an indispensable and powerful help in achieving that aim, by helping us maximize our human life potential, while bringing us nearer to the Life Divine.

References

1. The Mother. Collected Works of the Mother, Volume 3. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1977, p.198.

2. Sri Aurobindo. SABCL, Volume 19. Pon-dicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1970, p.896.

3. Op cit. Collected Works of the Mother, Volume 3. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1980, p.149.

4. Op cit. Collected Works of the Mother, Volume 5. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1976, p. 174-6.

5. Op cit. Collected Works of the Mother, Volume 9. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1977, p. 109.

6. Op cit. Collected Works of the Mother, Volume 15. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1980, p.170.

7. Sri Aurobindo. and Aphorisms. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2007, p.65.

8. Op cit. SABCL, Volume 20. Pondicherry; 1970, p.68.

Dr. Swarupa Nishar is currently a practising physical therapist in New York and, prior to that, was Chief Medical Officer at an Ayurvedic health centre in Goa.

Her husband, Mr. Govind Nishar, is currently serving as the President of the Sri Aurobindo Yoga Foundation of North America (SAYFNA) in New Jersey.

Share with us (Comments, contributions, opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH, and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.