Āyurveda

Śigru or drumstick (Moringa pterygosperma, Gaertn.,

M. oleifera, Lam.)

Abstract

The Śigru or drumstick tree is native to India. It is one of the most common household plants in South India and like many Indian plants is not only used for food but medicine as well. Here we rediscover a plant growing in our backyard!

This 25 foot tall tree is possibly one of the most useful in the world. It produces long green pods that have been compared to a cross between peanuts and asparagus. It has a delicate foliage and attractive pale white-yellow fragrant flowers. It grows best on dry sandy soil. This makes it an ideal shade tree with high drought resistance. The roots are used as a substitute for horseradish and its edible leaves make a highly nutritious vegetable. The roots have also been documented as being useful in many folk remedies. The flowers, shoots and foliage are all edible as greens. Cattle are particularly fond of them. Its young pods are cooked in curries. The seeds taste like peanuts when fried but contain an alkaloid, which limits their use. The unripe pods, known as ‘susumber’ or ‘drumsticks’, are cut up and boiled like beans. The coverings of the pods are extremely hard and fibrous and impossible to eat; one has to peel them off and eat the sticky pulp inside and the ‘pips,’ which are slightly hot and delicious. Upon pressing, the seeds yield an oil called ben oil. This non-drying oil is used for oiling machinery, in salad oils and soaps. The corky bark yields a gum, which is used in India to print calico (a cotton cloth with figured patterns).

Drumstick is of medical interest due to the compounds with potential clinical utility such as 4-alpha-L-rhamnopyranosyloxy benzyl glucosinolate. The seeds and fruits are used for water purification.

Botanically, it is called moringa after its Tamil name murunga and pterygosperma due to the seeds that are winged or oleifera due to its non-drying oil .

Names

The plant has many names in Sanskrit: śigru, śobhanjaña, kṛṣnagandhā, akṣīva. In English it is called horseradish and drumstick. In Hindi, it is sahijana, sanjana, munga. In Bengali, ojna; in Gujarati, surgavo, sekto; in Marathi, shevga; in Kannada, nugge; in Tamil, murungai; in Malayalam, mariha murunna; and in Telugu, munaga, mulaga.

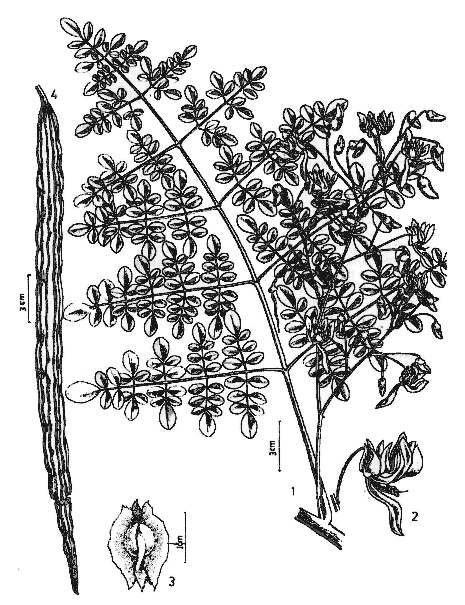

Moringa oleifera, Lam.:

1. A leaf with axillary inflorescence

2. Flower

3. Seed

4. Fruit

Courtesy: V.V. Sivarajan and Indira Balachandran. Ayurvedic Drugs and their Plant Sources. New Delhi; Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1994.

Botany

This is a pretty tree, the delicate tracery of its much-divided leaves giving it an airy, graceful appearance. It is very common in southern India where it may be seen in every back garden, waste plot or village. In the western Himalayas and Oudh, it used to grow wild.

The thick, grey bark is furrowed and comes off in corky flakes. The main flowering season is from February to April, but many trees can be seen in bloom from September onwards. The creamy white flowers appear in large, loose clusters, sometimes covering the whole tree in a white froth. Each individual flower is small; the stem bends sharply at the tip and nine of the ten long petals fold back around it. Six unequal stamens bear bright orange anthers. The old flowers turn rather yellow and, together with the new white flowers and pale green and white buds, the whole spray is a picture of delicate beauty, its sweet honey-scent an added attraction. The fruit starts as a pinkish, twisted tube and takes about three months to attain its full length of anything up to 20 inches, when it is bright green and ridged and contains many winged seeds. This extraordinary pod gives the tree its name of drumstick.

The soft wood yields a useful gum. The stems are very fragile and susceptible to frequent caterpillar attacks. The leaves are alternate but very characteristically compound to a great degree, that is, its main axis is branched many times, ultimately bearing thin, small and numerous leaflets. Such leaves are called decompound leaves. The leaves fall during the cold season. The leaflets are opposite and they have oil glands that are responsible for their characteristic smell.

Principal constituents

A chemical analysis of the leaves shows: protein 6.7; fat 1.7, carbohydrates 13.4, vegetable fibres 0.6, mineral matter 2.3, water content 75.0 percent; calcium 440 mg., phosphorus 70 mgs., iron 7.0 mg, copper 1.1 mg. and, importantly, iodine 51 per 100 gm. These leaves also contain carotene (provitamin A) 11,300 international units (I.U.) and vitamin B 12, 10 mg. (in every 100 gm.). The leaves are valuable because of their rich carotene, ascorbic acid and iodine content.

The pods also contain all these constituents and have 184 I.U. of carotene and ascorbic acid, 120 mg. (in every 100 gm.). They contain rich amounts of lucine, a nitrogenous compound. They also contain a few alkaloids.

The ash from the flowers reveals a considerable percentage of calcium and potassium. The seed residue after oil extraction makes a very good farm manure.

The roots contain an active antibiotic principle, pterygospermin. The root bark contains two alkaloids (total alkaloids, 0.1%), viz. moringine which is identical with benzylamine and moringinine belonging to the sympathomimetic group of bases. It also contains traces of an essential oil with a pungent smell, phytosterol, waxes and resins. An alkaloid, named spirochin, has been isolated from the roots (1). Hypotensive principles niazinin A, niazinin B, niazimicin, and niaziminin A and B were obtained from ethanolic extracts of the fresh leaves. These compounds are mustard-oil glycosides and are very rare in nature. They are rare examples of naturally occurring thiocarbamates (2).

Pharmacology

(From Himalaya herbal monograph)

An aquenous extract of M.pterygosperma in a dose of 200mg/kg disturbed the normal estrous cycle in rats, the response being duration dependent (3). Aqueous extracts of the roots and of the root bark of M. oleifera were effective in preventing implantation. The anti-implantation activity of the M.oleifera root was consistent regardless of its time and place of collection (4). The aqueous extract of the stem bark produced a dose dependent hypotensive effect on dog blood pressure. It failed to elicit any effect on isolated guinea pig ileum, rat stomach fundus or frog rectus abdominis muscle (5).

The methanol fraction of the leaf extract (at 100 mg/kg and 150mg/kg) was found to possess significant protective actions in acetylsalicylic acid, serotonin and indomethacin induced gastric lesions in experimental rats. A significant enhancement of the healing process in acetic acid-induced chronic gastric lesions was also observed with the extract-treated animals (6).

Pterygospermin (in concentrations of 0.5-3 µg./cc.) inhibits the growth of many gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria including Micrococcus pyogenes var. aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Aerobacter aurogenes, Salmonella typhosa, S. enteritides, S. paratyphosus Shigella dysenteriae, Mycobacterium phlei and M. tuberculosis var. hominis. In higher concentrations (7-10 µg./cc.), it is active against fungi. It is stable in the presence of blood and gastric juice but breaks down in the presence of pancreatic juice. Its effect is counteracted by thiamine and glutamic acid but reinforced by pyridoxine. It is toxic to experimental animals, but in low concentrations protects mice against staphylococcal infections. In view of its activity against moulds and fungi and its negligible effect on seed germination, pterygospermin may find application in the preservation of fruits and vegetables and in seed treatment (7).

Toxicity

(From Himalaya herbal monograph)

In cardiovascular profiles at lower concentrations (1-10mg), it produced a dose dependent positive inotropic effect and at higher concentrations (0.1-1microgm) a dose dependent negative inotropic effect on the isolated frog heart.

Indications

(From Himalaya herbal monograph)

Biological activity studies have confirmed the anti-inflammatory, anti-spasmodic and diuretic activities of the seeds. The seeds are used as anti-bacterial, anti-choleric and anti-viral agents.

Importance in traditional medicine

The seeds are called śveta marica or white pepper. They are acrid and pungent in taste and are used externally to remove joint pains in acute rheumatism.

The tree’s young roots are prescribed for many ailments such as intermittent fever, epilepsy, hysteria, palsy, chronic rheumatism, dropsy, enlargement of spleen and liver.

Hakims recommend the young roots for treating any soreness of the throat and pain in the gums due to dental caries.

In spirituous extracts, the root can be useful in treating fainting, giddiness, nervous debility, spasmodic afflictions of the bowels, hysteria and flatulence.

In Punjab, the gum is a popular remedy for treating rheumatism.

Many hakims advise using the fruit for liver and spleen complaints, joint pains, tetanus and nervous debility as well as paralysis.

The young leaves are used for treating dog bites, scurvy and the common cold.

The long pods are also reputed to prevent worm infection.

The flowers boiled with milk and sugar are presumed to be an aphrodisiac.

Yunani physicians regard the flowers to be hot and dry and beneficial for colds and swellings. They are also considered as a tonic and diuretic. They promote the flow of bile.

The flower juice with milk is prescribed for urinary stones and gravels and also for asthma.

Bhāvaprakāśa, a reputed Āyurvedic classic from medieval times, extols the use of a paste comprised of equal parts of the moringa seeds, rock salt, mustard seeds and goat’s urine as a snuff for arousing comatose as well as drowsy patients.

The oil of moringa finds an application in curing syphilitic wounds.

The bark of the root burns strongly when applied to the skin.

A decoction of moringa given with hing and saindhava salt proves beneficial in cases of rheumatism, convulsive fits and epilepsy, paralysis of the limbs, as well as in the enlargement of the spleen and liver.

Consuming drumstick as a regular article of food at frequent intervals helps stop rheumatism, impotency, nervous debility and constipation. It is also an insurance against roundworm infection.

Home remedies

(i) Add a fistful of tender drumstick leaves to two cups of boiling water. Close the lid of the vessel and let it simmer for five minutes. Keep the vessel in cold water and cool it down. Decant the juice into a separate vessel. Add a pinch of salt, pepper powder and lemon juice. Taking a cupful of this juice helps general debility, sexual weakness, nervous debility as well as common cold, bronchitis, ill-nourishment and anaemia.

(ii) To the leaf decoction add milk and sugar to taste. This forms a good beverage for children to purify their blood, improve health and also confer a general resistance to disease.

(iii) A soup with the leaves makes a very nutritious drink for pregnant women as well as nursing mothers. It is also very healthy and nourishing to all people ranging from infants to the very old.

(iv) Add a little lemon juice to the leaf decoction.

This works as a sure remedy for dizziness.

(v) In case of migraine, putting a few drops of leaf juice in the opposite ear helps.

(vi) A simple remedy for headache is a few grains of pepper, ground with a few drops of leaf juice, massaged on the temples.

(vii) A local application of paste of drumstick leaves and Calotropis (mudar) leaves relieves piles.

(viii) Hot fomentation with roasted drumstick leaves on injured swollen areas mitigates the swelling and pain.

(ix) The flowers boiled well in milk and taken with honey are a renowned aphrodisiac.

References

(From Himalaya herbal monograph)

1. Chopra et al. Indian J. Med. Res. 1932-3; 20: 533; Ghosh et. al., Ibid.1934-5; 22: 785; Chakravarti, Bull. Calcutta Sch. trop. Med. 1957; 5: 123; Chatterjee & Maitra, Sci. & Cult. 1951-2, 17: 43.

2. Caceres J. Ethnopharmacol. 1992; 36: 233; Chem Abstr 1993; 119: 529.

3. Shukla S. et al. Ind. J. Pharm. Sci. 1987; 49(6): 218-9.

4. Shukla S. et al. Int. J. Crude Drug Res. 1988: 26(1). 29-32.

5. Limaye DA. et al. Phytotherapy Research 1995; 9(1): 37-40.

6. Pal SK. et al. Phytotherapy Research 1995; 9(6): 463-5.

7. Rao et al. Nature, Lond. 1946; 158 : 745; Rao, Natarajan. Proc Indian Acad. Sci. 1949; 29B: 148; Kurup, Rao. J. Indian Inst. Sci.1952; 34A: 148; Kurup, Indian J. Pharm. 1952; 34A: 219; Rao, Kurup, Indian J. Pharm. 1953; 15: 315; Kurup & Rao. Indian J med. Res. 1954; 42 (85): 101; Gopalakrishna, et al. Ibid. 1954; 42 (97).

Selected reading

• Booth FEM,,Wickens GE. Non-timber uses of selected arid zone trees and shrubs in Africa. FAO, Rome: 1988, pp. 92-101.

• Jahn SAA. Traditional water purification in tropical developing countries: existing methods and potential applications (manual no. 117). Esschborn, Germany: GTZ; 1981.

• Jahn, SAA. Proper use of African natural coagulants for rural water supplies (manual no.191). Eschborn, Germany: GTZ; 1986.

• Morton, JF. The horseradish tree, Moringa pterygosperma (Moringaceae) — a boon to arid lands? Economic Botany 1991; 45 (3): 318-33.

• Nautiyal BP, Venkataraman KG. Moringa (drumstick) — An ideal tree for social forestry: Growing conditions and uses — Part 1. My forest 1987; 23 (1): 53-58.

• Ram J. Moringa, a highly nutritious vegetable tree, Tropical Rural and Island/Atoll Development Experimental Station (TRIADES), Technical Bulletin No.2, 1994.

• Ramachandran, C., Peter, KV,, Gopalakrishnan, PK. Drumstick (Moringa oleifera): A multipurpose Indian Vegetable. Economic Botany 1980; 34 (3): 276-83.

• Valia, RZ,, Patil, VK., Patel, ZN,, Kapadia, PK., Physiological responses of Drumstick (Moringa oleifera Lam.) to varying levels of ESP. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 1993; 36 (4): 261-2.

• Verdcourt, B. A synopsis of the Moringaceae. Kew Bulletin 1985; 40 (1): 1-34.

Dr. K.H. Krishnamurthy wrote about medicinal plants as used in the Indian context with deep interest.

Share with us (Comments, contributions, opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH, and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.

Antibacterial activity of water moringa

Antibacterial activity of water moringa