Psychology

Absent-mindedness, instinctive and wilful actions

Editor’s note

It is interesting to note the similarities between two systems of thought, especially when based on very different premises, such as the modern psychological understanding — rooted in a aterialistic biological paradigm — and the spiritual, which is based on direct experience and inner illumination. There is a certain convergence that occurs at the end of these different paths to the discovery of what lies behind the apparent facts of life. However, it is equally important not to be blinded by these similarities and forget some fundamental differences between the two separate lines. A basic point of divergence is about consciousness itself. Spiritual thought is guided by intuition, vision and experience; it regards consciousness as the fundamental stuff of existence and therefore capable of transcending instruments such as the brain. Modern psychology regards consciousness largely as an evolutionary by-product and therefore its evolution is linked to the evolution of forms and the materialbiological substratum. The spiritual paradigm however takes the stand that consciousness can be freed from its instruments, thereby awakening new possibilities of cognition and action. These possibilities, latent in every human being, are not yet recognised by modern cognitive psychology that sees thought as ultimate. Thus, though there are similarities in certain aspects of modern biological and spiritual views about certain processes, it is important to note that the details of how these functions operate are very different and so also the other and future possibilities. For a fuller understanding of this rather complex subject, the readers are also referred to Sri Aurobindo’s detailed exposition of this and related issues in Kena and other Upanishads, Collected Works, Volume 18, pages 48-62.

Introduction

In our daily lives, we perform many actions without complete cognitive control. You may drive the car while lost deep in thought and later exclaim that you can’t recall the route you travelled. Or you have the nagging feeling that you have forgotten to lock the door but after checking you discover that you had indeed locked it. The 19th Century American psychologist, William James gave the anecdote of a person who went to the bedroom to change clothes, but instead ended up going directly to sleep. This article examines the basis of such phenomena from the standpoint of cognitive psychology, neuroscience and integral psychology.

Cognitive psychology

The ability to perform skilled tasks without the need for executive control is referred to as ‘automaticity’ in cognitive psychology Investigation on this subject has picked up pace in the last few decades.

In the 1960s, Fitts and Posner articulated three stages of skills learning : (a) cognitive stage, during which the thought-process is involved in sense coordination; (b) associative stage, during which there is a gradual decrease in errors due to the development of correct sensory intuition; and (c) autonomous stage, during which the learned skill is performed with little or no conscious thought or attention (1). Atkinson and Shiffrin were among the first to incorporate control processes in their memory model. Posner and Snyder drew the distinction between automatic activation processes which occur without intention, conscious awareness or other mental activity and the conscious control processes which occur during goal-directed behaviour. Shiffrin and Schneider, through their experiments on visual search and attention, concluded that there appear to be indeed two different processes involved in attention; one which can be quickly adapted by the subject’s conscious intentions and the other which runs off automatically beyond conscious control. Norman and Shallice proposed an extended schema-based model consisting of two distinct processes: willed control and automatic control (2). More complex architectures have been proposed such as the CogAff Architecture Schema by Sloman, and the 6-layers architecture by Minsky.

Neumann summarised the three primary criteria of automaticity on which most two-process theories agree:

1. Automatic processes operate without capacity and neither suffer nor cause interference. This is generally but not always true.

2. Automatic processes are under the control of the stimulus rather than the control of the intentions of the person. In other words, you are unable to resist the stimulus and respond instinctively.

3. Automatic processes operate below the level of normal mental awareness. There are three identifiable variations here, the most extreme being the situation where the entire ’automatic’ action can be executed without any awareness. These are known as ’slips of action’ or absent-mindedness, examples of which were given in the opening paragraph.

Bargh outlined the ’four horsemen of automaticity’: awareness, intention, efficiency and control, and pointed out that mental processes are not exclusively automatic or exclusively controlled, but occupy a spectrum combining the features of both (3). Suffice it to say that the two-process theory of willed and automatic control has been accepted as a core construct in modern-day cognitive psychology (2, 3, 4, 5).

More generally, psychologists have developed various models of attention: bottleneck theory, attenuation theory, early selection theory, late-selection theory and feature-integration theory. These models will not be discussed here.

Neuroscience

Neuroscientists have been seeking to establish the neural basis of automaticity through brain imaging experiments. The results they have obtained vary depending on the nature of the task (sequential, random, dual-task, etc.); however, some general conclusions can be drawn from their experiments.

Neuroscientists have discovered that as we become adept at a task, the brain engages new regions to perform the task. The acquisition of a new skill is mediated principally through structures in the front of the brain (pre-frontal cortex), but as the task becomes ’automatic’, it is the motor structures in the middle and rear of the brain that assume a dominant role. This shift is specific to recall of an established motor skill and suggests that with the passage of time, there is a change in the neural representation of the task and that this change may underlie its increased functional stability (6, 7).

On a related note, in a famous lecture given in 1884 on the ’Evolution and dissolution of the nervous system’, neurologist John Hughlings Jackson had proposed a layered view of the nervous system, in which the brain is seen as implementing multiple levels of sensorimotor competence. He divided the nervous system into lower, middle and higher layers, and proposed that this sequence represented a progression from the ’most organized’ (most reflexive or instinctual) to the ’least organized’ (most modifiable). The Jacksonian view predicts dissociation between the higher and lower level components, such that lower level competence is left intact by damage at a higher level. Discoveries of such dissociations were amongst the earliest findings of neuroscience and are now understood to abound in the vertebrate nervous system. For instance, it has been demonstrated that removing the cerebral cortex from a cat or a rat — thereby eliminating many major sensory, motor and cognitive centres — leaves intact the ability to generate motivated behaviour. The animal still searches for food, eats to maintain body weight, shivers when cold, fights or escapes when attacked, and so on. These behaviours appear awkward and clumsy when compared to controls and are often poorly adjusted to circumstances. However, the ability to generate appropriate, motivated action sequences is retained. When most of the forebrain is removed, complete behaviours can no longer be produced, but the capacity for individual actions such as standing, walking, grooming, and eating is spared. With all but the hindbrain and spinal cord removed, the animal cannot coordinate the movements required for these actions — for instance, it cannot stand or walk unaided — however, most of the component movements that make up the actions are still possible. Similar results have been observed in several classes of vertebrates leading to the widely accepted conclusion that the anatomically lower levels of the vertebrate nervous system organize simpler movements, while higher levels impose more complex forms of behavioural control (8).

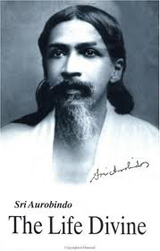

Integral psychology of Sri Aurobindo

Is there any ’consciousness analogue’ to these elaborate investigations undertaken in the fields of neuroscience and cognitive psychology? Although Sri Aurobindo did not specifically use appellations such as ’automaticity’, there are glimmerings of a theory in his works. In his prime phil-osophical work, The Life Divine, he wrote:

“What happens when the conscious becomes subconscious in the body or the subconscious becomes conscious? The real difference lies in the absorption of the conscious energy in part of its work, its more or less exclusive concentration. In certain forms of con-centration, what we call the mentality, that is to say, the Prajnana or apprehensive consciousness almost or quite ceases to act consciously, yet the work of the body and the nerves and the sense-mind goes on unnoticed but constant and perfect; it has all become subconscious and only in one activity or chain of activities is the mind luminously active. While I write, the physical act of writing is largely or sometimes entirely done by the subconscious mind; the body makes, unconsciously as we say, certain nervous movements; the mind is awake only to the thought with which it is occupied. The whole man indeed may sink into the subconscious, yet habitual movements implying the action of mind may continue, as in many phenomena of sleep; or he may rise into the superconscient and yet be active with the subliminal mind in the body, as in certain phenomena of samādhi or Yoga trance (9).”

Sri Aurobindo seems to tie ’automaticity’ to the withdrawal of prajñāna. In order to absorb the implications of the passage above, some background into his model of consciousness needs to be developed. Sri Aurobindo’s cognitive model is an extension of the model expounded in Vedanta, basic information of which can be obtained in the two-volume set on Indian Psychology by Jadunath Sinha (10).

In the Aurobindonian model, the basis of cognition in ordinary human beings is said to be the apprehending power of consciousness which works in two successive stages — saṁjñāna and prajñāna:

1. saṁjñāna is the incoming movement of apprehension where the sense-mind apprehends a stimulus and conveys the information towards the higher cognitive mind.

2. Prajñāna denotes the outgoing movement of apprehension where the object is imaged within and acted upon by the higher mind.

Sri Aurobindo expatiated on the greater power of saṁjñāna which enables one to act automatically in certain situations:

“Similarily we know that a large part of our physical action is instinctive and directed not by the surface but by the subconscious mind….” According to integral psychology, the mind is a distinct entity and “not merely an ignorant nervous reaction from the brute physical brain. The subconscious mind in the catering insect knows the anatomy of the beetle it intends to immobilise and make food for its young and it directs the sting accordingly, as unerringly as the most skilful surgeon, provided the more limited surface mind with its groping and faltering nervous action does not get in the way and falsify the inner knowledge or the inner will-force (11).”

“To return to the Vedantic words we have been using, there is a vaster action of the saṁjñāna which is not limited by the action of the physical sense-organs; it was this which sensed perfectly and made its own through the ear the words of the unknown language, through the touch the movements of the unfelt surgeon’s knife, through the sense-mind or sixth sense the exact location of the centres of locomotion in the beetle (12).”

How does saṁjñāna-prajñāna relate to the two-process models of cognitive psychology? It seems that when we are engaged in conscious willed control, the action of prajñāna and the action of saṁjñāna are coordinated with each other; the sense-mind intuits the stimulus and conveys the percept to the higher mind which then acts on it. By contrast, during automaticity, the power of prajñāna ceases (as Sri Aurobindo pointed out above) while the action of saṁjñāna remains active.

Conclusion

On the basis of the preceding discussion, it is possible to arrive at the modest conclusion that there is some similarity between the two-process models proposed in mainstream psychology and the prajñāna-saṁjñāna model clarified by Sri Aurobindo.

1. The automaticity phase defined in cognitive psychology is similar to the case where saṁjñāna becomes disconnected from and acts independently of prajñāna.

2. Willed control in cognitive psychology is similar to the case where saṁjñāna and prajñāna act in concert.

References

1. Fitts, P., Posner, M. Learning and skilled performance in human performance. Belmont CA; Brock-Cole, 1967.

2. Styles, E. The Psychology of Attention. Hove, UK; Psychology Press, 1997.

3. Bargh, J.A. ‘The Four Horsemen of automaticity: awareness, efficiency, intention, and control in social cognition’ in Wyer, R. S. Jr., Srull, T. K. (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition. Hillsdale, NJ; Erlbaum, 1994, pp. 1-40.

4. Cohen, J. D., Aston-Jones, G., Gilzenrat, M.S. ‘A Systems-level perspective on Attention and Cognitive Control’ in Posner, M. (ed.) Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention. 5. Kihlstrom, J. ‘The automaticity juggernaut’ in Baer, J. Kaufman, J.C. Baumeister, R.F. (Eds.), Are We Free? Psychology and Free Will. New York; Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 155-80. 6. Shadmehr, R., Holcomb, H.H. Neural correlates of motor memory consolidation. Science August 8, 1997; Vol. 277 no. 5327: 821-5.

7. Poldrack, R.A. et al. The Neural Correlates of Motor Skill Automaticity. Journal of Neuroscience; Vol. 25: 5356-64.

8. Prescott, Tony J., Redgrave, P., Gurney, K. Layered Control Architectures in Robots and vertebrates, Adaptive Behaviour; 7:99-127.

9. Sri Aurobindo. SABCL, Volume 18. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1970, p.183.

10. Sinha, J. Indian Psychology: perception. London; Kegan Paul Trench Trubner & Co. Ltd, 1934. One volume can be accessed at 11. Op. cit. SABCL, Volume 12. Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1971, p. 193.

12. Ibid. p.194. Author’s note

Vijñāna and Ajñāna are not discussed here and have been covered in another article, ‘The Epistemology of perception’ published in the November 2010 issue of Sraddha, a quarterly journal published by the Sri Aurobindo Bhavan of Kolkata. Sandeep Joshi is a computer engineer currently living in the India. He writes an Integral Yoga blog at http://www.auromere.wordpress.com Share with us (Comments,

contributions, opinions) When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH, and give the byline.

Please send us cuttings.