Social health

Cultivating an Ecological Consciousness

Abstract

This article talks about the human disconnection from Nature and how it is causing pathologies in man. It provides various solutions that eco-therapists can use and which can be taught in schools to develop ecological intelligence. Some of the solutions already exist as traditional ecological knowledge and have been re-purposed for modern situations. Some have been invented by residents of urban nature-less zones. But above all, this article invites people to tune themselves in to the nurturing vibrations of Mother Earth and her gifts of flowers and trees, not just for their personal well-being, but for the future of the planet. There is an urgency in this calling, for man has wronged nature long enough and, in the process, has hurt himself the most.

Ecological unconscious

For many centuries, a large portion of humanity has lived segregated from nature in technological Faraday cages, insulated from bugs and germs, and beauty and sentience. The natural world does not penetrate their habitat; and the concrete, steel and petrochemical lifestyle keeps her away. She peeps in as creepers in cracked walls and shakes humanity with her weather tantrums. But before this age, when she is regarded as a woman who needs to be tamed, she was worshipped as a mother and goddess. Five hundred years of the Age of Reason is twenty generations, which is a long time. Now the rational man, tormented by pathologies, cannot find medicines that cure his mental problems using mental techniques alone. When he allows plants and animals to come into his life, he begins to unravel these problems. The mind sits at the feet of the wise old ways, begging to be cured.

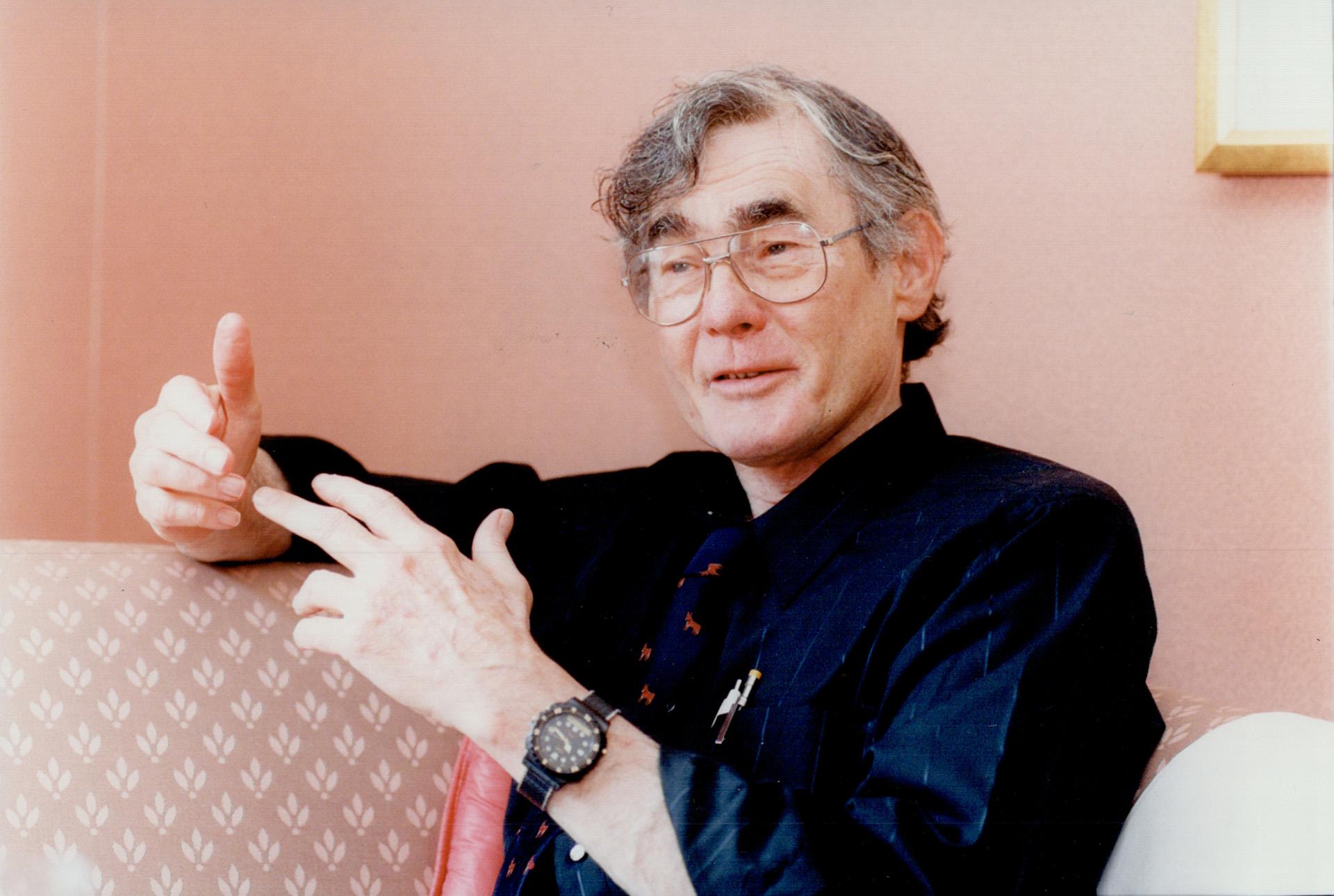

One of the pioneers in the field of eco-psychology, Theodore Roszak (1), calls the human bond with Nature the “ecological unconscious”. Just as the collective unconscious of psychology, we are born with this collective angst, as though it is part of our genetic material. Even if we were lucky to be nurtured in an eco-friendly society, when we move to techno-cities, we imbibe it from the field. This field is created by the thoughts and feelings of people sharing a common space, which get transmitted to others, without their being aware of it. There is denial, guilt, helplessness, nostalgia, anger, fear. The pathologies show up in dreams as something we are chasing but cannot find. We may see doomsday images of ashes and volcanic fires. Forests burn down and animals run in all directions.

All these scenes are occurring somewhere, and even if we are unaware of them in our waking state, they affect the system, of which we are a part. We erupt on our family members for minor reasons, and we cannot explain our actions. Sometimes we feel incomplete even if we have every conceivable material need met. We sense a natural disaster that is occurring far away and it causes us panic attacks. Our literature mirrors our state of disconnect. There is a taste for horror, for gore and blood, for unnatural pleasures, for wickedness, for destruction, for causing pain and feeling no remorse for it.

Self-healing remedies

To remedy our own ecological discomforts, we start connecting with the secret life of plants and creatures. We read literature that connects to nature. We read mythologies, folktales, and children’s literature. Mythologies around the world have Nature as characters in their drama. Daphne turns into a laurel tree in Greek mythology; an eagle fights the abductor who is stealing the queen Sita in the Indian epic, Rāmāyaṇa. We participate empathically with the people whose lives are being uprooted, say, due to new hydro-electric power plants or mining projects. We protest the destruction of the habitat of birds and forest creatures, and of forest-dwellers such as honey-makers and herbal medicine-gatherers. If the hydro-electric power plant solves bigger issues, we think of alternative habitats for the displaced people. If the timber is cut for luxury items, we voice our indignation, we take them up with the authorities, we involve environmental scientists to weigh in. Even if we do not participate in these movements directly, we fight for their cause in spirit. We become advocates in our circle of influence. The small talks in social gatherings veer around these issues, and we spread the awareness. Someone who is tormented by ecologically-induced pathologies can then take appropriate action. To apply Traditional Ecological Knowledge, TEK, we can learn from indigenous elders in our community, or in other regions of the world. This way the knowledge is preserved and propagated.

Fortunately, not all land-based cultures are completely uprooted. There are Elders in most indigenous communities who are holders of knowledge. Some communities honour them as shamans and go to them as a last resort when all treatment fails, as is mentioned in the story of the man who was bitten by a poisonous snake and became a cripple until he met a shaman who used “magic” to cure him (2). The Amazonian people, who mix the exact two plants from hundreds of species to produce the ayahuasca potion, know the formula because the spirits of the plants talk to them. Medicine men in Central America ask the permission of plants before they pluck medicinal herbs from them. The spirit of the plant is deified, or rather it is seen as it truly is — a divine being. Pacific island sailors know how to sense the distance from land when out at sea by watching and listening to the sound of waves against their boats. Predicting rain and harvest were done by nature specialists by reading the position of stars. These survival techniques are valuable memes that need to be passed down, just as a language needs to be passed down to safeguard certain truths that can only be expressed in that language.

Political ecology

Some practices from the land-honouring age of civilisations have been passed down the generations. In modern times, often they are performed as rituals and their meanings are forgotten. One of them is called, Itu poojo, worship of the Sun. A few weeks before the planting season, seeds of various grains are grown in a small pot. The grains that germinate are the ones to be planted for that season. It is considered as nature’s message that she favours this species of rice or lentil for this season in this region. But industrial agriculture is deaf to these messages.

Firstly, native species are not grown, because agricultural science, based on statistics gathered in some other country, dictates that such or such a crop needs to be planted. Secondly, there are governmental pressures on farmers to buy seeds from just a handful of multi-national companies. Thirdly, the seeds are tampered with genetic modification. The goal is short-term high yield, but at the cost of soil depletion and nutritional quality. Some of these non-native species need fertilisers, and more water than the land can provide. Monocultures are forced down on farmers to increase yield.

Monocultures are not nature’s way of growing food. A variety of plants forming a food basket need to be considered to measure yield. A balanced diet needs this basket, not just the staple crop. To counter ecological injustice eco-activist Vandana Shiva has created a granary-cum-training centre, where she collects indigenous seeds she can distribute to farmers, and also train people to do conscious farming. She is tapping into the wisdom of the old ways. Her centre is called Navdanya, which is a short name for Nava Dhanya, meaning “nine grains.” These are the nine grains that ancient Indian wisdom said would benefit both human and soil health.

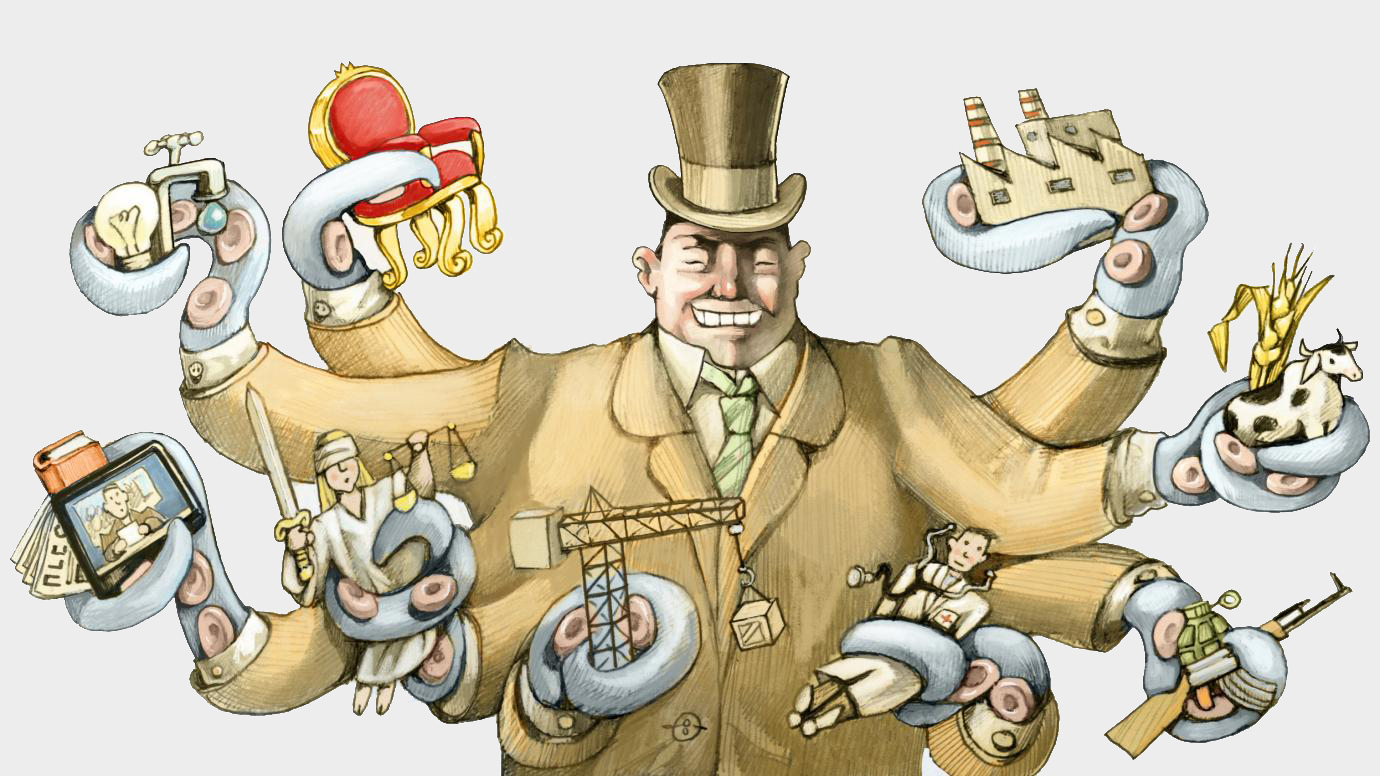

Corporate agriculture is a many-headed hydra. The Green Revolution of the 1980s was a loan package for developing countries from the developed nations, to buy the seeds and fertilisers supplied by the loan-granters. This does not sound much different from selling weapons to the Third World to solve their internal conflicts. The profiteering cartels are from the same places, and the victims are the same. The neo-colonised nations lose their native seeds, their soil gets polluted with chemicals, the water gets depleted as the foreign strains need more water. Above all, the food is nutritionally poor and adulterated. Only for the sake of quantity of harvest is such a high price paid. When the monoculture is a cash crop such as cotton, the entire region can suffer famine because food is not grown any more. Often the data used to prove suitability of a crop is inapplicable to the particularity of the land. The glamour of numbers is intimidating, just as a person wearing a suit can be, in a room where the others are wearing plumes and homespun.

Another battle to reclaim indigenous land and knowledge is the battle against bio-piracy. The technique of making basmati rice and the medicinal value of neem, to take two examples, were developed centuries ago in India. The patent office is a new phenomenon, a baby of technocracy. Although it sounds incredible that these products and methodologies can be appropriated and patented, this is a battle eco-activists have to fight. The patent filers are in the West, where these two genera of plants do not even grow (3).

Another sinister fall-out of modernity and its fruit, capitalism, is the world food problem. It is not because of shortage, but because of improper distribution, as many economists point out. Grains are dumped in the ocean to control the stock market prices, while a nation that has had a bad season starves. Essential commodities are traded as service commodities, which is another reason farmers get wiped out in a day. The value of their labour is laid to waste because someone with monetary power can decide to dump the stocks of a certain essential commodity. Starvation is also caused by forcing communities to grow cash crops at the expense of food crops. When flowers fetch more money from European auctions than rice that feeds the natives, farmers choose to grow flowers. History repeats itself when left to market forces. In 1848, in East India, millions died of a man-made famine. The reason was that rice was then replaced with indigo plantations. Indigo was the first dye for cotton yarn, and was highly sought after in Europe. Indigo and opium were the cash crops of that age. The narrative has hardly changed, although nations are now free, and therefore free to practise free trade.

To protect against food insecurity, governments have put policies in place. They are most often: local crop protection; price control, a public distribution system and common granaries; subsidies and incentives to farmers. These techniques are practised by all nations, whether socialist, authoritarian communist or capitalist democracies. Developed nations that knocked on the doors of Asian countries to open up their markets and go bullish on capitalism, are themselves protecting their own farmers by restricting imports. Let us consider the example of India to illustrate the governmental measures in place to counter market forces and monsoonal irregularities. There is a governmental price control on essential foods such as rice, lentils, cooking oils, sugar. The government buys these products from private farmers and stores them in granaries across the country. Each family gets to buy a certain quota of these products at an affordable price. These measures were implemented after several years of crop failure and famine. As for subsidies, most countries give cheap water and electricity to farmers, and grant generous loans. But no government can protect its people from natural disasters. Earthquakes, tsunamis, long-term droughts, massive floods, — are moments when humanity realises the enormous power of the Being they wanted to outsmart.

Nature is intelligent

Nature is smart and sentient. She listens to humans and provides healing if we give her the chance. She fades away and dies if she is ill-treated psychologically. She reacts to aggressors and can protect herself. There are many ways plants show evidence of intelligence. Some of them are propagation manoeuvres, distress signalling or healing a sick member. Plants fix nitrogen in the soil and enrich it for future generation of plants. Mother redwood trees provide nutrition to daughter trees through the roots. The mycelia, a fungi network under the earth, senses a sick tree and channels nutrients to her. This same network of fungi can cure depression in a human being when they touch the soil with their bare hands. The edges of roots are the brains that probe around the soil and take the path that is best for the plant (4). The mechanisms in which some plants form symbiotic relationships with others who can be their host, is another amazing phenomenon. When bugs come to eat a plant, this attacked plant secretes a smell that attracts the enemy of the bug. This is pure cunning and a marvel. The plants match the attacking pest’s chemicals to its predator insect or bird. When we catalogue the different ways in which plants propagate themselves, we are left amazed and wonder how we ever marvelled at human technological inventions. There are helicopter seeds that float in air. Some have corkscrew-like endings that burrow into the earth where they land. Oak seeds are so strong they can travel long distances in the stomach of animals, untouched by digestive acids. A forest fire is needed to pop open the seeds. They are naturally preserved for posterity. Humans now imitate these with ‘seed bombing’. Seeds are covered in a shell of clay and scattered, sometimes from helicopters, to cover a wide area. The seeds use rain and sunshine to anchor themselves and grow into trees (5). Learning from nature and adopting her ways is called biomimicry and it is a growing movement, full of empathy and gratitude for nature.

Individual action

With the consciousness of plants seeping into mainstream discourses, thanks to global warming, people are taking individual and collective actions to fight ecological devastation. There is a growing group of gardeners in the most congested and built-up cities of the world, not to mention the most polluted cities. Balcony and terrace gardening are common. Indoor plants are creeping in homes and offices. These individual planters have formed a social networking system where they help each other by providing tips and connecting buyers to sellers. The techniques of aeroponics and hydroponics are spreading.

Gardening has many benefits — healthy eating being just one. Soil has a property of curing depression and relieving stress. Plants become friends, or babies one tends to. One does not feel lonely. One gets into a flow state when gardening (6). I interviewed a friend who calls herself a ‘plantaholic’. She has a large patio garden in Delhi, one of the most polluted cities in the world. She likes the challenge of growing difficult plants. She has no children of her own and I believe all her motherly love is showered on plants. She feels proud to show off her thriving children, and anxious when a plant child gets sick. She rushes home to check on it after a workday. She buys special screens to adjust the sunlight on her plants. When I asked her about the effect plants have on her, this is what she shared:

“The joy and challenge of being able to root a cutting. Once it roots, fondly remembering the person who gave me the cutting every time I see the plant. The joy of seeing a new leaf, tightly curled, slowly unfurl and stretch itself. The joy of seeing a seed germinate. For days and weeks, there’s only soil and suddenly you see a shoot. Often, the seed is still on the shoot, perched like a rakish hat. The joy and challenge of figuring out the different needs of the different plants — water, light, sun, pH level of the soil, air. The absolute beauty of the different colours, shapes, textures.

“The patience gardening engenders — you can't hurry a plant along. Composting for my plants, knowing I'm reducing our landfill contribution, and the smell of fresh earth after the compost is ready. And pests too, knowing that they too are part of the cycle of growth and decay. Learning about companion plants and beneficial insects. For example, now I look forward to the blue banded Australian bee, which haunts my Dieffenbachia around this time — don't know why the bee likes that plant. And because I watch trees and plants so much, I slowly became a by-the-by birdwatcher too, and realised that Delhi isn't just home to crows, mynahs, pigeons. It has an astonishing variety of birds. Exasperation with myself for not figuring out why some plant isn't doing well. And sometimes, but very rarely, with the plant — some are total divas — to be fair to them, they are genetically programmed to grow on the Amazon Forest floor and here you are, trying to coax them to live in a smoggy city with 5-10 Celsius winter temperatures and 40-45 Celsius summer temperatures. Bewilderment: you’ve tried it all — full shade, full sun, semi-shade, filtered sunlight; water regularly, water only when the top two inches of the soil are dry, water only the leaves, water just the base; provide more nutrition, add more sand or perlite for better drainage; and yet some plants don't do well. I have liberally stood in front of my Senecio Rowleyanus and asked her, ‘What do you want?’ Awe: when you see the mind-boggling variety of plants? Admiration: the way a seedling struggles up through the soil. Pity: when my tomato plant was attacked by four pest varieties all at once.”

Community action

At the community level, common gardens have helped entire communities thrive. The food benefits are the least of the benefits. There is a variant of community gardening called ‘guerrilla gardening’. Ron Finley, from a depressed neighbourhood in Los Angeles, tells in his TED talk how he became a guerrilla gardener (7). The people in his community were suffering from curable diseases because they could not buy good food. They were paying more for medicines than healthy food. Los Angeles has a lot of empty plots. He picked one in his neighbourhood and started planting. When the fruits and vegetables grew, he told people anyone could take them. If they wanted to help him, they could come with a shovel. This had many salutary effects on the community. Work done voluntarily is itself a source of joy; it is fulfilling, non-judgmental, and enhances one’s life with new meaning. The youngsters who could have become gangsters worked the land to produce food. It is an act of creation as fulfilling as producing a painting. Ron Finley calls himself a graffiti artist. His medium is the soil and plants his paintings. Not only did crime reduce in the community, the people became physically and mentally healthy. Working the plants helps one tune in to the subtle vibration of plants. Gradually this becomes a numinous connection that touches the soul. Healing then occurs spontaneously. Those who have difficulty associating with people begin to relax and communicate at a deeper level with others. They feel a sense of achievement which brings self-confidence with it.

The first government sponsored community gardens in the United States were called ‘Victory Gardens’, grown by veterans who returned from the World Wars after the victory of the Allied Forces. They were employed to bridge the food gap, but greater benefits were discovered in their overall state of being. Now there is research evidence to prove how PTSD can be treated by communion with nature — be it gardening or hanging out with nature (8). Community gardens are used to train youth in growing plants. This training helps them appreciate the effort that goes into planting, growing, harvesting and transporting food to their homes. It makes them conscious of not wasting food. It also encourages them to choose local over transported food. When one sees one’s neighbourhood looking beautiful, one feels happy. At the same time people who become conscious of the food cycle, take to eco-stewardship and demand systemic reform. Eco-therapists are increasing in number and conventional therapists are bringing in nature into their therapy room or sometimes doing the therapy in a natural spot.

Cultivating an eco-friendly consciousness

The love for plants does not stop there. It becomes a love for all creatures, especially those that are victims of human exploitation. One becomes a spokesperson for habitat preservation, saving the whales and elephants from poaching, saving the earth from carbon emission and fracking. It does not stop there either. One feels like re-learning the culture of elders whose knowledge could have saved the earth from its present state of environmental depredation.

One goes to stay in eco-villages, such as Sadhana Forest in Auroville, India. Every year, hundreds of students from all over the world live for a few weeks in this permaculture-driven community and learn techniques of water efficient irrigation, clean energy, and other sustainable methodologies. They bring back their knowledge to their communities and green their turf. Sadhana Forest is in Auroville, which is an international community experimenting on human unity. The founder of Auroville is a spiritual figure called the Mother. She was born in France as Mirra Alfassa, and spent the last fifty years of her life in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, where she was the ‘Managing Director’ and Spiritual Guide. She was a trained occultist and could communicate with the natural world.

The Mother could sense the special vibration of every flower. She gave each a spiritual name, such as dahlias were Nobility, the pomegranate flower, Divine Love, the yellow chrysanthemum was Life Energy, and jasmine, Purity, and so on for hundreds of flowers, including the flowers of vegetables. When an unnamed flower was brought to her, she could feel the vibration of the flower and sense its essence (9). When she went to the garden, vegetables that were ripe cried out, “Me! Me! Me!” and all she had to do was pick them (10).

The school she established in the Ashram is well-tuned to nature. Once a week, the children attend a class in an estate some 20 miles from the city. Here they get to work in the gardens and learn botany. During the harvest season, they help with the harvesting. They are taught about cows and hens by looking at these animals in the farm. There is an aquarium maintained by the students who are diving enthusiasts. A group of dogs loll around the school, and play with the students and have become community pets.

Flowers from the many gardens are brought to the ashram where a team of ladies make garlands for floral decorations. In India jasmine garlands are worn by ladies as hair ornaments and hung in cars as protective talismans. Flowers are offered to deities in temples and homes; and the flower market is as busy as a vegetable market.

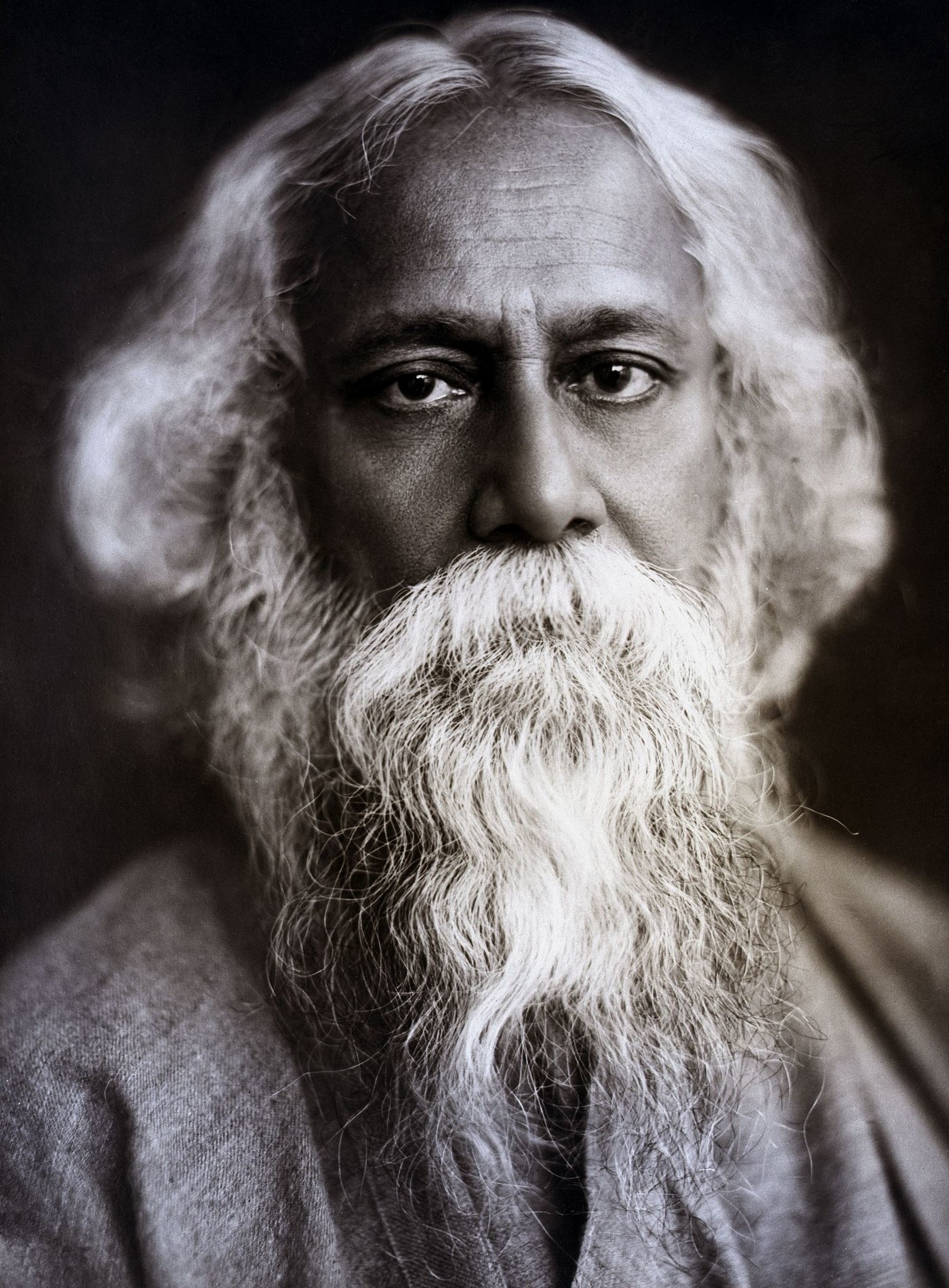

Another community that emphasises nature-based education is Shantiniketan in West Bengal. This was started by Rabindranath Tagore, one of the most famous poets of modern India. Here students sit under trees for classes. Art students have ample scope to draw village life as the university is in a rural setting. In the annual spring festival, women dye their sarees orange by soaking them in a solution of night jasmine flowers. They make ear-rings, necklaces and crowns of flowers. A song and dance performance follows that invokes Spring, personified and deified.

Conclusion

Once we start loving our Mother Earth, we begin to reclaim her and at the same time a neglected part in ourselves too. We then connect to this Being and listen to her deeply, we ask her how we can become instruments in her healing. She may answer us differently depending on where we live, what power we command and our inner capacities. She may ask one to concentrate on planting trees, collecting seeds, distributing to different communities. To another she may ask to write stories to spread the message of the R’s — recycle, reduce, re-use, repair, refuse. Another may hear that activism is her calling. She could join one of the many groups or form her own chapter. She could contact her local newspaper or the government representative. Another may want to become a professor of eco-psychology, or an eco-therapist. Someone may want to organise nature camps for children, or work as a volunteer to clean up the roads, the beach, or hiking spots.

When I started learning about eco-therapy, I found a shift in my consciousness towards nature. There is now a heightened awareness of nature’s beauty and her intelligence. I can connect with friends who have green thumbs and find their plant-love to be fulfilling. I appreciate my parents better since they have been growing plants all their life on land that was bigger than the plot on which they built our house. As they grow old and find it hard to work on the land, they tend to potted plants and spend a lot of time nurturing them. Our house has vases of flowers all over. My parents brought flowers from the market that we did not grow at home, such as lotuses and lilies. As these bloomed, they created an atmosphere of charm at home.

The Ashram in Pondicherry is one of the most decorated places on earth and every piece of decoration is a flower. Several gardens grow flowers just for the Ashram. The inner chamber has ikebana experts doing artwork every day, balancing the shape and colour of the vases with the flowers of the season, choreographing with the other vases and creating an awe-inspiring beauty. To think that each flower has a special spiritual significance and that they are pouring out their qualities to whoever can receive them is an overwhelming thought. One can only kneel in gratitude and pray for Nature to be healed and lead humanity towards a harmonious future.

References

1. Roszak T. ‘A Psyche as Big as the Earth’ in (ed) Buzzell L, Chalquist C. Eco-therapy, Healing with Nature in Mind. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint; 2009, p. 36.

2. [Online] Available from: http://eje.wyrdwise.com/v4/EJE%20v4_Tindall.pdf [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

3. [Online] Available from: Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3d9k23UyQQ [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

4. [Online] Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/stefano_mancuso_the_roots_of_plant_intelligence [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

5. Messer Diehl ER. ‘Gardens that Heal’ in (ed) Buzzel L, Chalquist C. Eco-therapy, Healing with Nature in Mind. pp. 166-73.

6. [Online] Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CrrSAc-vjG4&feature=youtube [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

7. [Online] Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/ron_finley_a_guerilla_gardener_in_south_central_la [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

8. [Online] Available from: https://www.academia.edu/35025390/The_effects_of_Ecotherapy_on_Stress-related_disorders [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

9. [Online] Available from: http://www.blossomlikeaflower.com/2008/01/questions-answers-by-mother.html#myLink1 [Accessed 24th August, 2023].

10. The Mother., Mother’s Agenda, Volume 9. Paris: Institut de Recherches Évolutives [English Translation]; 1980, p. 28.

Lopa Mukherjee is a psychologist and educator. She conducts workshops and teaches culture, soft skills and related subjects. She lives in Pondicherry.

Share with us (Comments,contributions,opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH,and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.