Āyurveda

Managing imbalance to prevent and cure disease: the approach of Āyurveda to life, health and longevity

Abstract

The doṣas are the pillars that support the body and, for this reason, their instability leads to the destruction of the body itself. The doṣas are unstable by nature and prone to imbalance. A continuous reconstruction of the body is necessary to keep the doṣas in balance for our health and longevity. Āyurveda makes us recognise the imbalance underlying disease in both early and advanced stages of affliction, helping us to prevent and manage diseases more effectively.

Vāta, pitta and Kapha are termed as the three doṣas. They destroy the body when deranged and sustain it when in a normal state. Doṣas represent the most basic of the technical terminologies that we have to be acquainted with in order to learn and apply Āyurveda in our lives. The concept of the tridoṣa points out that the life line of the body is also the fault- line. This is the great paradox of life. Whatever is responsible for the sustenance of the body is also responsible for its destruction. The term doṣa itself conveys this concept. Doṣa means ‘fault’. Why are the doṣas called so? What are the doṣas’ faults if they are responsible for the sustenance of the body?

How can the pillars of the body be called faults? The reason is that the body will eventually perish because of the very factors that sustain it in the first place. The balance of the doṣas cannot be maintained for ever. In due course of time, they will go out of balance and cause the death of the physical body. The body is managed by factors that will eventually fail it. Since the body is designed for self-destruction by a process of internal breakdown of the factors that are responsible for its maintenance, these factors are called doṣas.

They are called doṣas or faults because all pathologies are initiated by the imbalance of the doṣas irrespective of whether the causative factors operate from within or without. To survive, the body has to constantly adapt and adjust to changing circumstances. The doṣas are the factors that facilitate and execute the adaptation. There is no disease as long as the body succeeds in adapting to changing circumstances. When the doṣas are incapacitated, the body fails to adapt. When there is failure to adapt, then the body perishes.It is interesting to note that in the classical texts of Āyurveda, the word doṣa has been used to denote the factors responsible for the sustenance of the body. This is a warning that the physiological mechanisms of the body are susceptible to imbalance and breakdown. On the other hand, the body has been referred to as deha. The word deha is derived from the root dih upacaye, which means that which continuously reconstructs itself. While the doṣas have a tendency to break down, the body is trying to reconstruct itself perpetually. Sustaining that inner drive for the continuous reconstruction of the body is the key to health and longevity.

The cradle that nurtures life can turn into a grave in no time. The doṣas can make and break life. Life is stable and fragile at the same time. One moment it looks stable and in another moment, it becomes fragile.This is the challenge that nature has thrown before us. It is the challenge thrown at human freewill. A conscious choice has to be made. We have to keep the doṣas in balance. In fact, we should not allow them to behave like doṣas (faults) but rather as guṇas (merits). Āyurveda is necessary because we have to know how to keep the doṣas in balance. Āyurveda is possible because we can learn how to keep the doṣas in balance. But the very factors that sustain the body are faulty, because they have a tendency to derange and destroy the body. This is the bad news.

However, the good news is that the body is constantly engaged in an attempt to reconstruct itself. By strengthening this process, we can keep the doṣas in check and prolong lifespan and health span.

The classical teachings of Āyurveda are just an elaboration of this fundamental message. The entire teachings of Āyurveda explain what deranges the doṣas and what keeps them in balance as well as how to bring back the doṣas to balance when they get deranged.

What we do with our mind and body makes the difference. Even a wrong thought or emotion can imbalance the doṣa. For example, vāta is disturbed by lust, sorrow and fear. A wrong behaviour can imbalance a doṣa. For example, vāta can increase by keeping awake at night. A wrong diet can imbalance the doṣa. For example, vāta can increase by eating pungent, bitter and astringent substances.

But before we learn how to balance the doṣas, we need to understand the nature and behaviour of the doṣas itself first.

• Vāta is derived from the root, vāgatigandhanayoh. This means the principle of movement and sensation. In other words, vāta represents the ability of the body to sense external stimuli and respond to them.

• Pitta is derived from the root, tap santape. This means to heat and transform. Pitta represents the principle of transformation and represents chemical reactions that happen in the human body.

• Kapha means kena jalena phalati iti. This means, that which expresses the function of water. It is the principle of nourishment, support and structure of the human body.

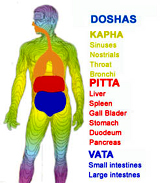

The doṣas have not been defined, but their characteristics are being described at the outset. The doṣas pervade the entire body. Yet vāta is specifically associated with the region below the heart and navel, pitta with the region between the heart and navel and kapha with the region above the heart and navel. vāta, pitta and kapha dominate in the last, middle and first phases of one’s lifespan, day and night as well as the process of digestion.

This means that the fault-lines are ambient. Every part of the body is susceptible to breakdown even as every part of the body has the capability to express life. Life and death go together. Construction and destruction go together. The doṣas destroy and create simultaneously. The body is constantly renewed until it breaks down eventually.

In spite of the all-pervasive nature of the doṣas, they are also localised in specific regions of the body at the same time. Strangely, the heaviest of the doṣas, kapha is localised in the head, followed by pitta in the central part and vāta, the lightest of the three doṣas is located in the lower part of the body. This phenomenon is counter-intuitive. How can kapha remain in the top and vāta at the bottom of the body? How is this possible and what is the purpose of this arrangement?

The human body represents the pinnacle of evolution. Plant life is fixed on the earth and under the grip of gravity. In human life, there is a 180 degree transformation. The human being is like a tree turned upside-down — ūrdhvamūlamadhaḥśākham ṛṣayaḥ puruṣaṃviduḥ. From plant life to human life is a movement that turns life upside-down. Kapha, representing earth and water, is now located in the top of the human body. And vāta representing the atmosphere or air and space is in the lower part of the body.When the human being stands with his or her head held high, he or she trumpets the victory over the lower forces of gravity and the promise of soaring into the heights of the mental world and beyond. How was this upside-down posture achieved by humans in the process of evolution of life? What are its consequences and most importantly, what is its purpose?

The doṣas pervade the entire body. Yet vāta is specifically associated with the region below the heart and navel, pitta with the region between the heart and navel and kapha with the region above the heart and navel. When plant life turned 90 degrees upside, animals emerged. When animal life turned 90 degrees upside, humans emerged.

The arrangement of the doṣas in the human body makes it appear like a cooking-pot of sorts. Vāta in the lower part of the body can be compared to the bellows that fan the flames of the digestive fire. In the centre of the body is the internal fire that transforms the ingested food into the substance of our bodies.

Optimal activity of vāta in the lower limbs is essential for strengthening the digestive fire. The more we move our lower limbs, the more the fat in the body is burnt and the stronger the digestion becomes. Walking briskly while swinging the arms is therefore, one of the best exercises that activates vāta, stimulates pitta and reduces kapha.

Kapha or the watery element in the upper part of the body works like a coolant and keeps the heat of the body in control. If kapha increases in the lower limbs, it is pathological. The feet become swollen. Swelling caused by kapha in the feet can even be the sign of a fatal disease. If kapha increases in the abdomen, then it is a sign of obesity. Central obesity can invite life-threatening diseases. The major natural seats of kapha are all located in the upper part of the body. Minor imbalances of kapha are common in this area like the common cold, which are not very threatening disorders. However, severe imbalance of kapha in this region can be life-threatening.

If vāta increases in the upper region of the body, it can cause severely debilitating degenerative diseases affecting the nervous, pulmonary or cardiovascular systems. Pitta imbalance in upper region can also lead to severe and debilitating inflammatory conditions. Minor and frequent imbalances of pitta are more common in the middle part of the body like hyperacidity, which can also become severe and problematic if persistent in the long run. Minor and frequent imbalances of vāta are more common in the lower part of the body like muscle cramps. In spite of the fact that there are exceptions to these general observations, the mapping of the doṣic dominance in the upper, middle and lower regions of the human body provides a preliminary framework for understanding patterns of disease manifestations.

There is a difference between imbalance of the body elements and manifest disease. Imbalance of the doṣa, dhātu1 and malas2 constitute the basis for all diseases. One disease differs from another only in terms of the nature of the imbalance. Therefore, in Āyurveda, the focus is on understanding the imbalance rather than the manifestation of the disease. That is why Āyurveda has defined disease as dhātuvaiṣamya3. Imbalance is the cause and disease is the effect. Health can be established only by correcting the underlying imbalance of the doṣas, dhātus and malas. That is why in Āyurveda we can get results even without targeting the disease. Imbalance of body elements can exist even without disease. But disease cannot manifest without an underlying imbalance. The goal of Āyurveda is to prevent an imbalance from translating itself into disease. In modern medicine, a disease is diagnosed only when the imbalance has been translated into a manifest pathology that can be detected by objective diagnostic methods.

1 Literally the supports of the body, representing the seven elements of the body that constitute the structural components of the body — plasma, blood, muscle, fat, bone, marrow and reproductive tissue.

2 The gross and subtle waste-products of the body.

3 Imbalance of the body elements.

Dr. P. Ram Manohar is Director of Research, at the Amrita Centre for Advanced Research in Ayurveda, Kollam, Kerala.

Share with us (Comments,contributions,opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH,and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.